This is the story of how Peter Thiel’s father and Klaus Schwab ensured that tens of thousands of black slaves & their family members were eaten to death by radiation.

In 1967, Peter Thiel’s father, Klaus Thiel, was an expert in open-pit mining. When Peter Thiel was still an infant, his father was recruited by the apartheid South African regime to work on their clandestine nuclear weapons program. However, Klaus Thiel was not the only German named Klaus at this time who was working on the secretive South African plan to develop a nuclear weapon. A young Klaus Schwab was also doing business with the South African regime on behalf of the Model Nazi Company, which his father once ran, Escher Wyss.

In a previous article, “Dr Klaus Schwab or How the CFR Taught Me to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” I revealed that the founder of the World Economic Forum had received CIA-funded training under the tutelage of Henry Kissinger.

This article also reveals for the first time that the Rotary Club funded Schwab’s involvement in the infamous Harvard Seminar, a course that functioned as a CIA leadership training program. The article also reveals Klaus Schwab’s direct involvement with American nuclear scientists at the University of California, Berkeley. During this period, U.C. Berkeley was central to the US nuclear arms race, and Schwab was in CIA training.

In one of the saddest and most psychologically scarring articles I’ve ever researched and written, I explore the truth behind Thiel and Schwab’s involvement in a true crime against humanity. Be aware, some of what you’re about to read could devastate the hardest of hearts.

City of the Dead

Swakopmund had once been a hearty and relatively prosperous coastal town within German South Africa. During the First World War, the town was occupied by British soldiers. The Belfast Morning News of Friday, 19 March 1915, produced an article subtitled Glance at the Operations in German S.W. Africa which reported on the British Forces’ first impression of the town, stating:

“Handicapped in every possible way by nature, by an abominable landing-place, and by a site that is as sandy as the foreshore and the Hinterland, the Germans, by dint of the energy and thoroughness so characteristic of them, have reared a town which, in design and buildings, easily surpasses anything of the same size in British South Africa. They made up their minds to create a port, and they have done so—out of the worst possible material. In similar circumstances we should have said the thing was not worth while, and we should either have left the place alone altogether or else have dotted down enough corrugated iron shanties to carry on with. But that is not the German way. They have built themselves solid buildings—Government offices, warehouses, shops, and dwellings, which in such surroundings excite one’s wonder and envy”

When the British arrived in the German South African port, they were met with a ghost-town of sorts. They marched through the empty streets, which were described as a “veritable city of the dead” in the latter article. Swakopmund had only been developed over the previous two decades. In 1899, the town got a telegraph line for the first time, and according to the German press, Cecil Rhodes himself had become interested in the area. The Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette in February 1900 reported:

“According to the Berlin correspondent, Mr Rhodes will probably go to German South-west Africa in April, his visit being connected with the development of the Otavi mines and the Anglo-German railway project from Fish Bay or Swakopmund, in German South-west to the Transvaal.”

Even though the Otavi Mining and Railway Company was tied to the German Government, they had initially received a special concession not to connect Swakopmund to the German railway line. Instead, they planned to build a railway line from Swakopmund to Port Alexander, which the Portuguese then held. Otavi Mining had copper mines in the area, and, in 1903, they agreed to join the Otavi Railway at Karibib with the Swakopmund Windhoek Railway. The South-West African Company joined with German financiers in a £1,000,000 deal. Otavi Mining and Railway Company would complete the train line, and in return, they’d receive mining rights.

The following year, there was a more serious conflict in the region. Natives were reported as besieging the local army garrison at Okahandja. This was the start of the Herero and Nama genocide. In January 1904, Samuel Maharero and Captain Hendrik Witbooi led their people in an uprising against their German colonial rulers. They killed more than a hundred German settlers in Okahandja, and the retaliation by the Germans over the following 4 years was brutal.

Nama and Herero natives were systematically starved, dehydrated, and imprisoned in concentration camps, with between 34,000 and 110,000 people murdered in what was the first genocide of the 20th century. By November 1906, the Otavi Mines and Railway Company opened the new train line from Swakopmund to Tsumeb. The project had gone over budget, but soon the profits were through the roof. Within the first 200 tons of ore to be shipped to Europe, copper and lead were found to be in abundance. Out of the first 100 tons of ore which was smelted in Europe, 10-16% was copper and 30-50% was lead.

When the British Army arrived in the Swakopmund ghost town during World War I, they were also capturing strategically important mines while pushing out the perpetrators of the Nama and Herero genocide. Production at the facilities had increased markedly by this time. The mines at Tsumeb, Otjisongati, and Sinclair had become major sources for the mining of Copper, Lead and Silver, and they were shipping around 50,000 tons of ore a year.

Swakopmund became central to the British consolidation of British South Africa. In 1916, an expedition of British soldiers commanded by General Botha landed there, and advanced to Windhoek, the German Capital, to support the troops which had been occupying Windhoek since 12 May a year prior. The entire German force of 204 officers and 3,293 men stationed at Windhoek surrendered to General Botha in what was seen as a vital victory in the region.

However, retreating German soldiers had soured the victory in the Namib desert by reportedly poisoning the drinking wells as they fled. The Germans claimed to have left signs on each of the wells they poisoned to warn those who came of the dangers. The Union forces reported that many wells had been poisoned without any such warnings being provided. The British claimed to have found that bags filled with arsenic were being dropped into some of the wells, and, in response, the Germans counter-claimed they were actually bags of cooking salt.

After World War I, Germany was devastated, and Swakopmund began to be referred to as a former-German town. Yet, the white natives who were living in this region remained mostly of German ethnicity.

The Mines Are Eating Us

Like many prominent American military and intelligence assets post-World War II, Peter Thiel was not born in the United States. Thiel was born on 11 October 1967 in Frankfurt, Germany, to Klaus and Susanne Thiel. The family moved to Cleveland in 1968, but soon after relocated again to apartheid South Africa, where Klaus Friedrich Thiel oversaw the development of a uranium mine near Swakopmund, located in modern-day Namibia.

By the time Peter Thiel’s family relocated to the region, South Africa had already begun to develop its clandestine nuclear program. To successfully create a nuclear weapon, the South African apartheid regime had to complete certain tasks. Firstly, it had to find or exploit a source of radioactive material. Secondly, it had to process those materials to make the radioactive material weapons-grade. Thirdly, it had to use that weapons-grade nuclear material to create a viable nuclear warhead which could be delivered via a missile. Apartheid South Africa made at least seven nuclear weapons.

The history of uranium is inextricably tied to Swakopmund and Namibia more generally. It was supposedly Captain Peter Louw who first discovered uranium in the Namib Desert in 1928. However, the extraordinary size of the uranium deposits may not have been truly recognised until over three decades later. London’s Weekly Dispatch on 27 October 1957 printed a short article entitled “Big uranium find in Africa,” with the piece stating:

“Huge deposits of uranium have been found in the waterless Namib desert in South-West Africa by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer’s Anglo-American Corporation. The deposits are between 15 and 20 miles long and from a half a mile to a mile wide.”

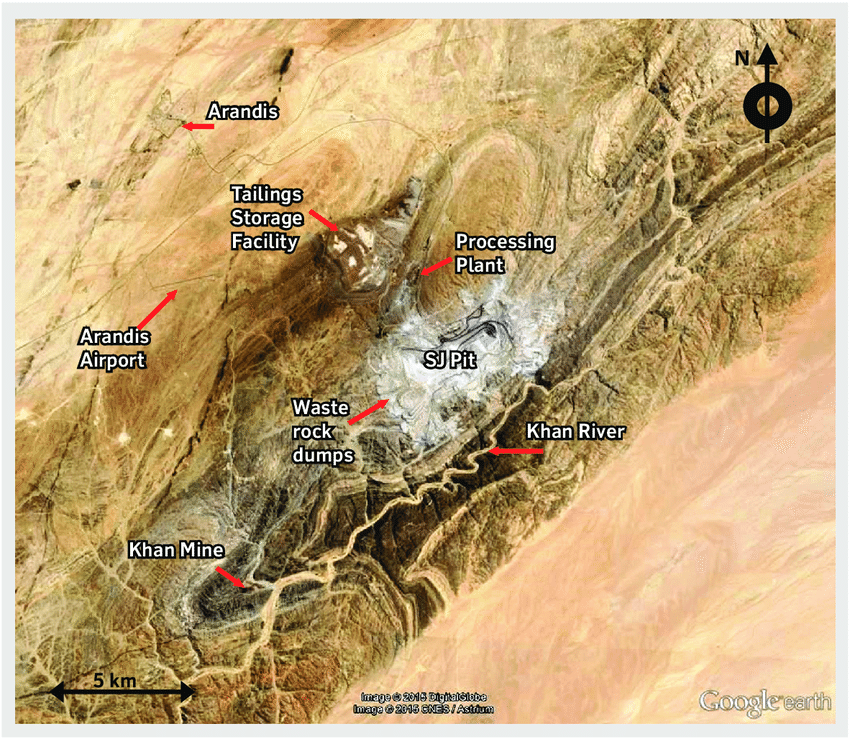

The Rössing uranium mine was officially opened in 1976 and was located 50km away from the coast, bringing jobs and prosperity to the region. However, the mine was actually being developed in secret, from at least the late 1950s.

The official story of the mine’s history is provided in the Namibian government document, Uranium 2022: Resources, Production and Demand, which states:

“With the upswing in the uranium market demand and prices, extensive uranium exploration started in Namibia in the late 1960s. Several airborne radiometric surveys were conducted, and numerous anomalies were identified. In 1966, after discovering uranium occurrences, Rio Tinto acquired the rights to the low-grade Rössing deposit, located 65 km inland from the town of Swakopmund on the Atlantic coast. Trekkopje, a near-surface calcrete deposit just north of Rössing and Langer Heinrich, another calcrete deposit situated 50 km southeast of Rössing, were also discovered during this period. Mining commenced in 1976 at Rössing and exploration intensified as uranium prices increased sharply.”

The Rössing uranium mine discovery wasn’t by accident. There was a big push to develop known uranium deposits during the 1960s. Five years prior, the Soviet Union had tested the largest nuclear bomb in history, the Tsar Bomba, an explosion which has still never been matched. However, there was an even more pertinent reason for the Western powers to develop more sources of uranium. In late August of 1964, Soviet scientists, led by Dr. Dmitry Ivanovich Blokhintsev, who had built the first nuclear power plant at Obninsk, synthesised element Number 104. It was described in the California newspaper, The Register, as “the 12th radioactive element heavier than uranium created by man since 1940.” The article goes on to say:

“The synthesis, he {Blokhintsev} said, was accomplished by hitting a plutonium target with accelerated ions of neon 22. If correct, this meant that Soviet scientists had finally achieved a feat that had eluded the best efforts of (among others) the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory of the University of California at Berkeley, the world’s leader in studies of elements heavier than uranium.”

On 7 September 1966, Dr Walter R. Hibbard Jr., the director of the US Bureau of Mines, arranged a meeting with Wilfred E. Johnson of the US Atomic Energy Commission and others to discuss the supply and demand of uranium.

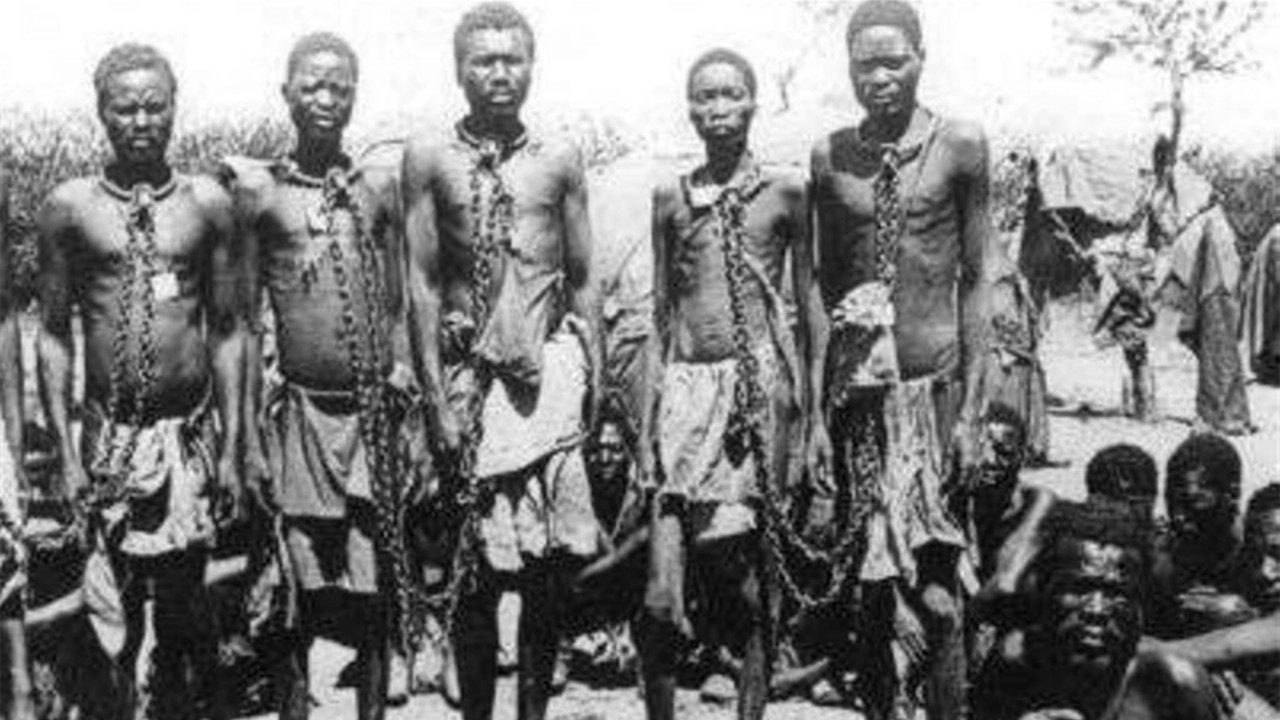

Klaus Thiel was assigned to the Rössing uranium mine while it was a key part of the South African nuclear weapons program. In his book about Peter Thiel, The Contrarian, author Max Chafkin notes that the mine used black forced labour at the site. Chafkin also writes:

“Klaus earned his master’s degree over the next six years, becoming a project manager who oversaw a team of engineers on mine projects. His speciality was the construction of open-pit mines, which involves excavating huge mounds of dirt and rock and then treating them chemically to extract minerals. The family moved frequently, and Klaus travelled even more, often spending weeks at a time on job sites far from home.”

Peter Thiel had spent his early childhood in Cleveland, but soon relocated to South Africa. The young Peter Thiel attended the elite whites-only prep school in Johannesburg, followed by a German-language public school in Swakopmund itself. Swakopmund was a difficult place to live for many black people. The white community honoured their German ethnicity during the time the Thiels were based there. The Guardian’s Chris McGreal reported on this in 2025, in an article entitled “How the roots of the ‘PayPal mafia’ extend to apartheid South Africa,” stating:

“At that time, Swakopmund was notorious for its continued glorification of Nazism, including celebrating Hitler’s birthday. In 1976, the New York Times reported that some people in the town continued to greet each other with “Heil Hitler” and to give the Nazi salute. Van Niekerk visited Swakopmund during South African rule. “I was there in the 1980s, and you could walk into a curio shop and buy mugs with Nazi swastikas on them. If you’re German and you’re in Swakopmund in the 1970s, which is when Thiel was there, you’re part of that community,” he said.”

Klaus Thiel was working on apartheid South Africa’s nuclear weapons program. The West South African mine was central to the clandestine efforts to obtain a nuke. In fact, the Rössing mine itself was in direct contravention of a United Nations resolution. Some workers later gave evidence that the project Klaus was in charge of was so secretive that some of the workers weren’t told that they were mining uranium.

The whites and blacks had very different safety protocols at the Namibian mine. Chafkin describes some of this unethical disparity:

“Uranium mining is, by nature, risky. A report published after the end of apartheid by the Namibia Support Committee, a pro-independence group, described conditions at the mine in grim terms, including an account of a contract laborer on the construction project—the project Klaus’s company was helping to oversee—who said workers had not been told they were building a uranium mine and were thus unaware of the risks of radiation. The only clue had been that white employees would hand out wages from behind glass, seemingly trying to avoid contamination themselves. The report mentioned workers “dying like flies,” in 1976, while the mine was under construction.”

In the 2021 book, Monstrous Ontologies: Politics Ethics Materiality, authors Caterina Nirta & Andrea Pavoni specifically drew on anthropological fieldwork conducted in Swakopmund—now referred to as the “Uranium Capital of the World”—and contrasted it to the works of Donna Haraway, Anna Tsing and HP Lovecraft. They describe their paper as situating “uranium as a god-like monster waiting in the desert for a time to arise.” The authors investigated the monstrous effects of uranium on the people of Swakopmund and the workers of the Namibian mines. The paper states:

“Indeed, to ingest uranium (known as internal exposure) would be to become monstrous through sickness, a process of ‘becoming uranium’, or at least the twisted by-product of working in the industry. This was mirrored in the way that mining was sometimes described to me as a commonality across linguistics: eemina oda ndituli, [Oshiwambo], mughodhi urikutidya [Shona], or libulu aliyaka nzoto na ngai [Linga], all translating as the mines are eating us. Whilst these phrases also refer to the economic exploitation that was often associated with mines and are specific neither to Swakopmund nor indeed Africa, in situ they vividly describe a particular effect of radiation on the body: the effect of being eaten alive, with the body weakened and slowly destroyed by seemingly invisible forces over long periods of time.”

Uranium had monstrous consequences, and people like Klaus Thiel knew the effects exposure to radioactive material has on the human body. Thiel’s involvement was during the very early development of the Rössing mine while it was still classified as South African. Rössing Uranium Limited was formed in 1970 to develop the Rössing uranium deposit. Rio Tinto Zinc was the leading shareholder with 51.3% of the equity when the company was formed, and subsequently increased its stake to 69%.

In 1978, the Rössing Foundation was founded, which, a 2016 OECD document says, was established to “focus on education, health care, environmental management and radiation safety in the uranium industry.” However, radiation safety was not something which was implemented for the black slaves who were forced to labour in the uranium mines before 1978. Evidence shows significant activity at the Rössing uranium deposit from at least 1957, meaning that, for over two decades, no significant safety measures were put in place for the black mine workers.

Tens of thousands of mine workers would have been exposed to deadly levels of uranium, and they would have brought the radioactive materials back to their families and their communities. The effects of exposure to radiation from uranium mining was already well known. In an article from 1966 entitled “Hazard Seen”, Washington’s Associated Press reported that 70,000 army wrist compasses were to be destroyed because the luminous dials gave off dangerous radioactive gas. Within the article, it states:

“Officials said radon gas has been a problem in uranium mines where, in poorly ventilated areas, miners inhaling the poisonous substance have over the years contracted lung cancer.”

The actual number of people who were injured or who died as a result of exposure to radiation from the Rössing mine is unknown.

For Nuke and Country

By 1976, it was being reported that the uranium being mined near Swakopmund was being used by the British nuclear deterrence program. In an article entitled “Namibia’s sawdust Kaisers,” journalist Neal Ascherson writes:

“Namibia is one of the mining centres of the world. The Canadians mine copper at Tsumeb, Anglo-Americans shovel diamonds from the dunes along the Skeleton Coast, and in the desert north of Swakopmund, Rio Tinto Zinc is digging the uranium which loads the British nuclear deterrent. More than diamonds, it is the great uranium mine at Roessing [sic] which gives the Foreign Office and the State Department doubts about their interest in the total independence of Namibia.”

It was clear that the British were heavily involved in the uranium mining which surrounded Swakopmund throughout this period. In another article by Ascherson, dated 25 January 1979, the author states:

“As the evening comes on, feral shrieks rise among the palms as English and Scottish engineers from the uranium mines at Roessing stagger from bar to bar. For fish suppers, they clutch fresh pilchards and chips done up in the Namib Times. The Germans loathe them.”

By March 1980, Britain’s involvement in the Namibia uranium mining was exposed. A Daily Mirror article by Ronald Ricketts entitled “How UN atom ban is beaten,” explained:

“Britain buys vast quantities of uranium from Namibia despite a United Nations ban, it was revealed last night. The UN ruled five years ago that the removal of the African country’s mineral resources should be outlawed. But Britain buys £500,000 worth of Namibian uranium a week from a mine partly owned by British-based Rio Tinto Zinc, it was claimed on ITV’s World in Action. Labour MP Tony Benn said that civil servants kept the deal secret when he was Technology Minister. When the secret came out, the government eventually gave its approval—but Mr. Benn thought he was “wrong not to fight it.” RTZ chief executive Alistair Frame said later the deal was legal.”

In the same month, the Daily Express produced a piece by John Ellison which said:

“It’s called Rössing… a rose-pink hole a mile long and nearly a thousand feet deep in the baking raw granite rocks of the Namib Desert, day and night, seven days a week, giant excavators claw at its terraces. Three thousand men, marshalled by British engineers, work in shifts through the 100-degree heat to ensure that Rössing’s huge processing plant, fed on crushed granite, never stops. A uranium mine—the biggest in the Western world—it produces each year 5,000 tons of U 308, a grey powder which fuels the nuclear power stations of Britain, France and Germany. In energy terms Rössing is a mini oil state. Its uranium is equal to about 500 million barrels of oil—two-thirds of our total yearly consumption.”

Swakopmund was just a few hundred miles north of the infamous offshore diamond fishing concessions, which were owned and controlled by the De Beers subsidiary called Consolidated Diamond Mining. South African gold mines had become close to unprofitable at the close of the 1960s. The fixed price of gold during this period at $35-an-ounce, and companies were prospecting for other potential commodities with a better market value. During the peak of the nuclear arms race, uranium prices were rising.

As the future Technocracy began to be created, the importance of developing nuclear power stations became beneficial in various ways, especially economically speaking. In an article for the Daily Telegraph entitled “South Africa’s rich successor to gold,” journalist Ray Kennedy writes:

“World demand for electricity is expected to rise to 1,080,000 megawatts by 1980, an increase of 1,000 per cent over the 1950 figure. Nuclear power stations will provide a high proportion of this extra power. The South African Government is therefore particularly interested in the discovery in United Nations-contested South West Africa of a massive uranium prospect. It has come about—for such is South Africa’s luck in this sphere—through diamond drilling operations at Rössing, near Swakopmund, on the South African coast.”

The South African Minister of Mines and Planning at the time, Dr Carel de Wet, confirmed that there were extensive low-grade uranium deposits discovered, which could be mined by the relatively low-cost open-pit methods. Of course, de Wet wasn’t telling the press the entire story. The South African regime had already developed the uranium mine, and the country was heading towards becoming a nuclear power.

South Africa was not acting alone during this period. The rise of nuclear technology is inextricably linked to both the rise of Globalism and the rise of the Technocracy. The fact that South Africa became central to the British nuclear program during this period could be viewed as either ironic or contrived. South Africa had been the birthplace of Cecil Rhodes’ Round Table movement, and a proud vassal of the Fabian-filled British Establishment; regardless, that is what happened.

Atomic Schwab

By 1966, Klaus Schwab had been noted by the American media as studying in the US, as the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported in July of that year:

“A young German Scholar, Dr. Klaus M. Schwab, visited here recently. He has been traveling through the United States before doing graduate work in the fall at Harvard. Dr. Schwab’s father is a customer of Texas Refinery Corp., headquartered here, and a TRC representative in Germany told Dr. Schwab he really wouldn’t be seeing America unless he went to Texas. So Dr. Schwab did. While here. He fell into the company of such TRC people as Drake Benthall and Roy Tavender.”

Schwab travelled to Texas by bus from New York, with the newspaper article remarking on his ability to spark conversation during his journey. However, the article didn’t mention that Klaus Schwab was actually in America to attend a CIA-funded program based at Harvard, which was run by Henry Kissinger himself. The following year, both the New York Times and Ramparts magazine exposed Kissinger’s International Seminar as funded by known conduits of the CIA, including from Kermit Roosevelt’s American Friends of the Middle East.

Klaus Schwab was already a German Rotary Foundation Fellow in 1966 and was invited to the Hotel Don to speak before the Richmond Rotary club in August of that year. An article for a California paper called The Independent also mentions that Schwab had been studying at U.C. Berkeley for six weeks before he returned to Harvard. There were several famous nuclear physicists associated with the University of California, Berkley during the 1960s.

The inventor of the cyclotron and the founder of the Radiation Laboratory, Ernst O. Lawrence, may have passed away almost a decade before, but he had built a strong legacy for the study of radiation at the campus. During Schwab’s visit, Edwin M. McMillan—who shared the Nobel Prize with Glenn Seaborg in 1951 for discoveries in trans-uranium elements—was serving as director of the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory from 1958 to 1973. His partner in crime, Glenn T. Seaborg, had served as the chancellor of U.C. Berkeley from 1958 to 1961 and was also deeply involved in research on trans-uranium elements. Emilio Segrè was another Nobel Prize winner who was focused on nuclear and particle physics. Another Nobel laureate, Luis W. Alvarez, was also at Berkeley during the 60s, and also focused on nuclear and particle physics, specialising in the use of bubble chambers to study subatomic particles.

Schwab would have arrived at Berkeley just in time to meet Thomas Bohr, the grandson of Niels Bohr. The Bohr family had spent the summer in Berkeley, and the university was treating them like nuclear royalty. Niels Bohr’s contributions were vital to the scientists in Los Alamos who had developed the first atomic bomb. Klaus Schwab would have also enjoyed the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory Museum at the time, which was exhibiting the bomb case of Little Boy, described in The Santa Fe New Mexican on 25 August 1966 as a “gun-type uranium weapon of the kind detonated over Hiroshima.”

Schwab was being awarded accolade after accolade during this period of his life. He worked as a consultant for both Bonn’s Federal Ministry of Economics and as a representative of the German Machine Builders. The latter article also mentions Schwab’s father, Eugen Schwab:

“His father is the immediate past president of the Rotary Club of Friedrichschapen, near the Alps.”

Like his father, Klaus Schwab took his Rotary Club Fellowship role very seriously, and the Rotary Club have serious questions to answer. The CIA-funded training program, which Klaus Schwab was attending at Harvard, had various reported funding streams. An article in The Morning Union paper from 22 May 1967 reveals that the Rotary Club was also involved in the Kissinger-led CIA program:

“An industrial consultant from Germany will speak at the weekly meeting of the Westfield Rotary Club today at 12.15 p.m. at Tonelli’s. Klaus M. Schwab, studying at Harvard Business School on a Rotary Foundation Fellowship, will discuss the international work of the Rotary Club.”

The Rotary Club has hosted talks from previous members who have also been high-ranking CIA officials, such as CIA Director William H. Webster at Phoenix Rotary Club in January 1988 and Lt General Vernon A Walters in 1975, who was CIA Deputy Director at the time. A CIA FOIA notes Lt. General Walters’ comments to a joint meeting of Rotary-Kiwanis Club in Columbus, stating:

“CIA, he said, is the “eye of the giant” – the eye which, if blinded by needless probing into top secrets by outside agencies, will frighten our allies and please leaders of countries who do not wish us well. General Walters, who speaks eight languages and has been an advisor to many Presidents and Ambassadors in his 34 years of service, pointed out that many people think of CIA as an instrument of war. He calls the agency “a weapon of peace.” Because of CIA’s monitoring capabilities, we have been able to reach an agreement with USSR on intercontinental ballistic missiles, he said; and expressed optimism for the future of international relations, especially with Brazil, which he calls a rising super-power. General Walters quoted CIA’s motto: “You shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free.”

Klaus Schwab went on a mini tour of Rotary Clubs while in the States, including delivering a talk to American Rotary Club members in Massachusetts in 1967. The meeting was reported in The Springfield Union, in an article entitled “Nazism Rise Said Minor In Germany”, which stated:

“Expected to finish his studies here next month, Schwab said he will spend a month in Washington, before returning to his home in Germany in July. He said the past year spent in this country “will have a great influence on my future activities and on my life.”

The article also mentions again that Klaus Schwab had been awarded a Rotary Foundation Fellowship to attend Harvard for the 1966-1967 academic year. The month before the previous article was released, The New York Times revealed that the course Schwab was attending during this period was CIA-funded.

From 1968 onwards, Klaus Schwab was recruited by his father’s Model Nazi Company to head a merger and illegally sell nuclear weapons technology to the South African apartheid regime. In the same year, Klaus Thiel was also heading to South Africa after he finished his travels with Uwe Finger, and moved his fledgling family unit to Swakopmund.

Klaus Schwab attended Kissinger’s International Seminar at Harvard between 1965 and 1967. Kissinger’s Seminar was the precursor to the WEF’s Forum for Young Global Leaders. These programs were originally designed to train potential leadership candidates, who could later be installed into positions of power after CIA-supported coups, colour revolutions, or within companies with an interest in the deep state.

Kissinger was central to America’s nuclear endeavours. After writing Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy in 1957, Kissinger became the go-to political mover for anything related to the proliferation of nuclear technology. The other big name in nuclear theory during this period was the Hudson Institute’s Herman Kahn. Often described as the “Real Dr Strangelove”, Kahn conceived of the notion of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) in 1961, and these men became two of Schwab’s mentors. In fact, on Klaus Schwab’s return to Germany after the Kissinger course, he was sent back with both Herman Kahn and famed economist JK Galbraith to set up the World Economic Forum, initially called the European Management Forum.

However, on Klaus Schwab’s return in 1967, Peter Schmidheiny asked him to help with the restructuring of Schwab’s father’s old company. Escher Wyss had been central to the Nazi nuclear weapons program during World War II. They didn’t only design the casing for a potential atomic bomb, they also created the massive turbines which were used for creating weapons-grade nuclear materials.

Escher Wyss had garnered a negative name for itself after helping the Nazi regime. In the late 60’s, the company were merging with a company called Sulzer AG, with the company temporarily being called “Sulzer Escher Wyss”. Klaus Schwab turned Sulzer Escher-Wyss into a modern technology corporation which would design significant parts of our hi-tech future.

As I reported in Schwab Family Values, Escher-Wyss pioneered some of the most important technologies in power generation. As the US Department of Energy points out in their paper on Supercritical CO2 Brayton Cycle Development (CBC), a device used in hydro and nuclear power plants, “Escher-Wyss was the first company known to develop the turbomachinery for CBC systems starting in 1939.” Going on to state that 24 systems were built, “with Escher-Wyss designing the power conversion cycles and building the turbomachinery for all but 3”.

By 1966, just before Klaus Schwab began to work for Escher-Wyss, the Escher-Wyss helium compressor—designed for the La Fleur Corporation—continued the evolution of the Brayton Cycle Development. This technology was still of importance to the arms industry by 1986, with nuclear-powered drones being equipped with a helium-cooled Brayton cycle nuclear reactor.

Escher-Wyss had been involved with manufacturing and installing nuclear technology at least as early as 1962, as shown by this patent for a “heat exchange arrangement for a nuclear power plant” and this patent from 1966 for a “nuclear reactor gas-turbine plant with emergency cooling”. After Schwab left Sulzer Escher-Wyss, Sulzer also helped to develop special turbo compressors for uranium enrichment to yield reactor fuels.

When Klaus Schwab joined Sulzer Escher-Wyss in 1967 and started the reorganisation of the company to be a technology corporation, the involvement of Sulzer Escher-Wyss in the darker aspects of the global nuclear arms race became immediately more pronounced. Before Klaus became involved, Escher-Wyss had often concentrated on helping design and build parts for civilian uses of nuclear technology, e.g. nuclear power generation. Yet, the arrival of the eager Mr Schwab coincided with the company’s participation in the illegal proliferation of nuclear weapons technology. By 1969, the incorporation of Escher Wyss into Sulzer was completed, and the merged companies were rebranded as Sulzer AG, dropping the historic name Escher-Wyss from their name.

It was eventually revealed, thanks to a review and report carried out by the Swiss authorities and a man named Peter Hug, that Sulzer Escher-Wyss began secretly procuring and building key parts for nuclear weapons during the 1960s. While Schwab was on the board, the company also played a critical key role in the development of South Africa’s illegal nuclear weapons programme during the darkest years of the apartheid regime. Klaus Schwab was a leading figure in the founding of a company culture which helped Pretoria build six nuclear weapons and partially assemble a seventh.

In the report, Peter Hug outlined how Sulzer Escher Wyss AG (referred to post-merger as just Sulzer AG) had supplied vital components to the South African government and found evidence of Germany’s role in supporting the racist regime, also revealing that the Swiss government “was aware of illegal deals but ‘tolerated them in silence’ while supporting some of them actively or criticised them only half-heartedly”. Hug’s report was eventually finalised in a work entitled: “Switzerland and South Africa 1948-1994 – Final Report of the NFP 42+ commissioned by the Swiss Federal Council” which was compiled and written by Georg Kreis and published in 2007.

By 1967, South Africa had constructed a reactor as part of a plan to produce plutonium, the SAFARI-2 located at Pelindaba. SAFARI-2 was part of a project to develop a reactor moderated by heavy water, which was fuelled by natural uranium and cooled using sodium. This link to developing heavy water for the creation of uranium, the same technology which the Nazis had utilised, also with the help of Escher-Wyss, may explain why South Africans initially got Escher-Wyss involved. By 1969, South Africa abandoned the heavy water reactor project at Pelindaba because it was draining resources from their uranium enrichment program that had first begun in 1967.

Nuclear Apartheid

The Thiel family only left Swakopmund in 1977, briefly returning to Cleveland before settling in California. Klaus Schwab and Peter Thiel are similar in various ways.

They are both the progeny of engineers who used slave labour to further the nuclear weapons programs of genocidal regimes. Schwab and Thiel are also responsible for designing and implementing major parts of the Technocracy, which is springing up around us. Schwab has done this through the World Economic Forum, and Peter Thiel via Palantir, Thiel Capital, Thiel’s Founders Fund, Mithril Capital and his many other tentacles. There is also another similarity. Peter Thiel was taken under the wing of Irving Kristol and the Neoconservative Elite, and Klaus Schwab was taken under the wing of Henry Kissinger and others at Harvard.

In 1967, the mockingbird media began to reveal the many CIA programs running out of Harvard University. The Six-Day War had changed the CIA’s focus considerably; Israel now had the full backing of the United States military and intelligence establishments. There was an opportunity for a proverbial reset, and the American Elite grasped the opportunity. Harvard University’s deep ties to both the American political Establishment and its intelligence apparatus became so exposed during this period that they had to withdraw from such surreptitious activities temporarily. Instead, they handed these activities on to a new group of illicit actors, the Neoconservatives.

William F. Buckley was interviewed by Esquire magazine in January 1961, where he stated:

“I would rather be governed by the first 2,000 people in the telephone directory,” he said, “than by the Harvard University faculty.”

Only six years passed before the New York Times and Rampart’s magazine revealed the CIA’s funding of Kissinger’s International Seminar. Television programs such as In The Pay of The CIA revealed that Gloria Steinem had run her CIA-funded youth propaganda operations out of Harvard. As it was revealed to the people of America that Harvard intellectuals had become entangled with the creation of an overreaching deep state intelligence panopticon, wars like Vietnam were simultaneously turning public sentiment against the ideology of Kissinger et al.

In response to failing public sentiment, the prestigious Ivy League university handed the baton of state censorship, propaganda, and control over to the likes of Irving Kristol and his fledgling political ideology.

Neoconservatism had facets straight out of Trotsky’s playbook. An ideology which manufactured a state of permanent revolution wherever it was implemented. Henry Kissinger and his counterparts were the old iteration of the post-WWII deep state; Irving Kristol and the Neoconservatives were the new guard.

As I explained in the article Dr Klaus Schwab or How the CFR Taught Me to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Klaus Schwab was trained by Henry Kissinger himself through the CIA-funded Kissinger’s International Seminar at Harvard. On graduating from Kissinger’s seminar, Schwab returned to Europe with the grandfather of nuclear theory, Herman Kahn, and the famed American economist JK Galbraith as mentor. There, Schwab and his new American friends formed the original iteration of the World Economic Forum and began the march towards the Technocracy we now see developing around us. While the neoconservatives began creating non-governmental development organisations and think tanks targeting the Soviet Union, the old guard began preparing the ground for the new generation. Central to this new era of next-generation warfare was the controlled proliferation of nuclear weapons.

In 2019, Rio Tinto sold its 69% share of Rössing to the China National Uranium Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of the government-owned China National Nuclear Corporation. The Rössing mine is scheduled to close at the end of 2026.

It should be no surprise that the responsibility for creating illegal, illicit, or secretive nuclear weapons programs has been handed down from father to son. There is only a small group of Technocrats who can construct the Technocratic Panopticon, and they only have a tiny pool of elites to choose from.

If you want to understand the reasons for our current issues, ask yourself this: If you were to let the sons of evil, genocidal maniacs reform our society in their image, then what would our new society look like?

PLEASE SUPPORT THIS WORK – I NEED YOUR HELP TO CONTINUE PRODUCING IN DEPTH INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM – LIKE, SHARE, SUBSCRIBE & DONATE

One response to “Schwab and Thiel – Nuclear Apartheid”

Wow,

These historical revelations add NUCLEAR to an already pitch black elite order. I keep wondering what can I do? I’ve been on a long journey since 2016. Learning or unlearning everything I thought I knew about my country.

Your a gem…keep fighting the litigation of Rothschild gold-digger Junkerman.

LikeLike