The CIA’s Controlled Takedown of Jeffrey Epstein Part 2

Stanley Pottinger played a central role in signing off on Watergate, the Kent State Massacre, and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. As his time at the Justice Department came to an end, he also helped his good friend and CIA director, George H. W. Bush, in other ways. However, Bush was not Pottinger’s only connection to the world of intelligence during this period; he was also busy smuggling arms with Jeffrey Epstein himself. Welcome to the Pottinger Supremacy.

Pottinger had been the Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice from 1973, eventually standing down in 1977, where he became classified as a Special Assistant to the Attorney General for a brief period later that same year. In that position, Pottinger was allowed to stay on under the Carter administration to finish his official investigation into the Watergate scandal. In the years that followed, Pottinger initially worked as an attorney for large companies and some other, more sinister individuals before transitioning into banking. However, during this period of Pottinger’s life, his association with a specific three-letter US intelligence agency becomes unbearably obvious.

As J. Stanley Pottinger left government service; his mentions in the annals of history decrease. He was no longer the public face of an influential government department; instead, he moved on to join a reformed private legal practice, which was still finding its feet. On 5 August 1975, Troy, Malin and Loveland were formed and were registered initially at 324 Datura St., West Palm Beach, Florida. The named directors of the legal firm, Joseph F. Troy, Ronald H. Malin and Joseph A. Loveland Jr., didn’t start by practising law in Florida; they had all been based in Los Angeles, California, and that is where the practice had originally begun to see clients. Within a couple of years, Loveland Jr. became a Director, Vice-President and General Counsel for the hotel chain Ramada Inns, later going on to manage other successful enterprises and, by 1978, his old legal firm was being reformed into Troy, Malin and Pottinger (TMP).

In 1978, the State Bar Annual Report of TMP listed ten shareholders as part of the law firm. Still, by the following year, TMP only registered two shareholders, Troy and Malin, leading to an eventual court case in 1984 to establish who actually owned shares in the firm.

The King of Compliance

The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), also referred to as the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act, was passed by the US Congress on 26 October 1970. The act had been successfully pushed forward due to the efforts of Rep. Wright Patman, a Democrat of Texas, who, in the early 70s, was the chairman of the House Banking and Currency Committee. The law required financial institutions in the US to assist American government agencies in their efforts to detect and prevent money laundering.

In July of 1972, after an eight-month delay, the Treasury Department officially put the BSA-related regulations into the Federal Register, which enabled the law to take effect. However, by the 1980s, many institutions hadn’t changed their behaviour, with various groups claiming that the act violated Fourth Amendment rights protecting against unwarranted search and seizure, along with Fifth Amendment rights protecting due process. In 1977, the Treasury Department was prompted to enforce measures within the banking sector, and the following year, they were reportedly ready to take action.

In a New York Times article dated 23 January 1978, entitled “US, After Lapse, Is Enforcing Bank Secrecy Act,” the action being taken against various organisations was announced, stating:

“The Treasury, which last year fined Gulf Oil $229,500 for failing to report money it brought into the United States, is expected to bring further actions against other corporate violators including Lockheed and Phillips [sic], according to congressional sources.”

The article, written by Jeff Gerth, noted the recent troubles experienced by, among others, Chemical Bank, which in 1977 had been indicted on 445 counts of failure to report $8.5 million in cash which they had moved into the US. Gerth writes that many banks were also guilty of moving money, which “involved laundered funds of suspected narcotics traffickers.”

To tackle the growing risk of more serious indictments, companies such as Chemical Bank were looking for a legal representative who had significant and confirmed influence within the government. The latter article also states:

“Chemical Bank, in the wake of its indictment last year, instituted substantive changes in its operations. The bank, sixth largest in the nation, strengthened its auditing and compliance division and hired two former Justice Department officials —Harold R. Tyler Jr., former Deputy Attorney General, and J. Stanley Pottinger, former Assistant Attorney General in charge of the civil rights division. In an independent inquiry, the two men detailed various weaknesses in the bank’s monitoring and reporting techniques. As a result, the bank adopted new, tighter procedures.”

Pottinger was highly sought-after once he left the White House, and, in expanding his horizons, it wasn’t only Chemical Bank which enticed Pottinger to represent them. As advances in communication technology increased exponentially, so did the risk of harmful public exposure, potentially causing a scandal for any famous brand. This gave large corporations the impetus to revitalise their public image by creating highly skilled integrity checkers to examine their companies’ procedures for any potential significant issues. By early 1978, Pottinger had seen a growing gap in the market. The Atlanta Constitution reported on 7 May 1978 that:

“One government source, who has been closely tracking the upsurge in so called “corporate integrity investigations,” estimates that fully one-fourth of the nation’s “Fortune 500” businesses have hired outside law firms or financial detectives in an effort to rid themselves of everything from dishonest executives to infiltration by organized crime.”

The article goes on to say:

“Recently, for example, J. Stanley Pottinger, former head of the Justice department’s {sic] civil rights division, formed one such company in Washington with John Olszewski, the hard-nosed former head of the intelligence division of the Internal Revenue Service. When Pottinger’s law firm is hired to probe a large corporation, he simply contracts with his own company to do the actual investigative legwork.”

Pottinger had created a company with a former intelligence chief, offering large corporations internal investigations that could potentially uncover sensitive information and prevent public exposure. This was where Pottinger shone the most. While in public office, he had been the go-to guy for when the government needed to investigate itself and keep any potential revelations from becoming common knowledge. In relation to the Kent State Shootings, Watergate, and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Pottinger had not only spearheaded the investigations but also been responsible for the official cover-ups.

.In 1979, Pottinger’s law firm, Troy, Malin & Pottinger, was hired to represent some of the biggest companies in the US. The Mead Corporation were soon to hire Pottinger and his associates for their battle against Dr Armand Hammer’s Occidental Petroleum. The latter was attempting to acquire Mead Corp., an Ohio-based “forest-products company” which had turned to Pottinger and his legal partners to fight off an attempted takeover by Occidental. Troy, Malin & Pottinger’s involvement in the case had a devastating impact on Occidental’s attempted acquisition, forcing Hammer’s company to release a mass of damaging information during a five-month takeover struggle. An article by Judith Miller, published in the New York Times, stated:

“Mead’s anti-merger strategy, according to lawyers on the case, depended on either winning the antitrust actions or uncovering enough unfavourable information about Occidental’s business practices to force it to withdraw. To do the digging, Mead hired Troy, Malin & Pottinger, a firm with Washington and Los Angeles offices that specializes in combining litigation and investigatory skills. Lawyers for the firm decline to discuss the case. However, it was this firm, according to sources close to the case, that uncovered Dr. Hammer’s practice of soliciting undated resignation letters – a practice that raises questions about whether the Occidental board was able to carry out its statutory mandate to provide an independent check on management.”

By the time Pottinger and Co. deposed Occidental financial consultant, Maurie P. Leibovitz, Mead had won their freedom, and within a week of Pottinger’s aggressive questioning of Leibovitz, Occidental Petroleum abandoned their lengthy and pricey takeover attempt.

J. Stanley Pottinger had left his post in the Justice Department and wasn’t finding it difficult to gain work from corporate giants. However, during this period, Pottinger was also involved in the business of treason.

Pottinger’s Central Role in the Iran-Contra Scandal, Illegal Arms Smuggling, and the October Surprise

Pottinger’s connections to US intelligence agencies had become glaringly obvious by the start of the 1980s. In the office, he had helped cover up various brazen crimes committed by three-letter American intelligence agencies. During this period, Pottinger had also teamed up with a former intelligence head from the Internal Revenue Service. Still, it is his many connections to the CIA which really stand out. As previously mentioned in part one of this series, The Pottinger Identity, J. Stanley Pottinger had made sure George H. W. Bush’s CIA had gained the authority to begin limited domestic surveillance activities after the assassination of Orlando Letelier, but Pottinger was doing a lot more behind the scenes, and he was being watched.

To an outside observer, Pottinger appeared to be involved with his own political ambitions during 1980, running unsuccessfully as a Republican candidate in Baltimore’s 8th district of Bethesda. He was also giving public donations to political candidates during the 1980 presidential campaign, including contributions of $1000 to Edward M. Kennedy’s campaign, as well as $250 to the campaign of George H. W. Bush. If it wasn’t his own political ambitions which saw Pottinger make the newspapers in 1980, it was his relationship with the infamous feminist Gloria Steinem. Steinem, who also had many links to the CIA by this period, reportedly helped Pottinger decorate his new house on Helmsdale Road in Bethesda.

The interior decorator employed by Pottinger for this task was a contractor named Shelly Grant Gambler, who failed to complete the work, with Gambler’s business declaring bankruptcy soon after taking the contract and leaving Pottinger as one of several creditors. Pottinger requested that his case against Gambler take precedence over the other creditors in the bankruptcy case, claiming Gambler had defrauded him. The case was unusually handed over to the US Attorney’s office so that they could examine the agreement. If found guilty of fraud, Gambler was facing five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. However, in return for Pottinger dropping the case, Gambler offered him a $5,000 “promissory note,” which Pottinger accepted. Pottinger dropped his case against Gambler, claiming that his decision not to continue with the claim was unrelated to the $5,000 promise he had received from Gambler.

Throughout 1979, Pottinger had become a veritable man about town, often seen at the trendiest clubs, hanging off the arm of his girlfriend, Steinem. Pottinger was still to represent big clients in 1980, with a court case against the under-fire founder of Space Research Corp., Gerald V. Bull, dragging Pottinger into the limelight again. Bull was being reported as a “broken man” after he was convicted of illegally dealing arms to the South African apartheid regime. In jail, Bull was diagnosed as suicidal, and he was put under round-the-clock psychiatric care, which saw Pottinger successfully argue for a one-month delay to his client’s trial. Pottinger initially pushed for a reduction or the suspension of his client’s sentence, but the evidence was enough to see the beleaguered Bull heading towards a trial.

Bull had originally been charged in Canada for conspiring to send arms illegally to South Africa. Still, that case was soon settled with a settlement which stipulated that Bull couldn’t be indicted. However, on the other side of the border, Gerald Bull wasn’t going to find any such leniency. The day after a settlement had been announced in Canada relating to the illegal shipping of ultra-long-ranged artillery shells and other equipment to South Africa, the Green Bay Press-Gazette was reporting that federal officials were still investigating the case. Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti was in charge of the probe, which saw both SRC’s President, Gerald V. Bull, and its chief operations officer, Rodgers L. Gregory, plead guilty.

Gerald Bull’s Space Research Corporation (SRC) had originally gained its funding after the US and Canadian Federal Governments cut the budget related to his involvement in Project HARP (High Altitude Research Project). The joint Governments gave the remainder of HARP’s assets to Bull’s newly formed SRC to develop and commercialise the technology needed for superior long-range artillery.

SRC’s client list contained various nations which were swamped with controversy, with the authoritarian governments of China, Chile and South Africa being among their main customers. Bull had also supposedly received bolstering support from the CIA for some of his projects. South Africa was seen by the US intelligence agency as a potential bastion against the Soviet infiltration of Angola, with the CIA even being rumoured to have successfully persuaded South Africa to invade Angola at the start of their civil war in 1975.

It was after the UN mandatory arms embargo prohibiting the export of arms to South Africa was introduced in 1977 that Bull, again rumoured to be encouraged by the CIA, supplied the apartheid regime with gun barrels and 30,000 shells, which cost more than $30 million. The shipment of arms was delivered on the MV Tugelaland with the cooperation of Israeli Military Industries. Gerald Bull was eventually murdered in 1990; it is believed that his death was at the hands of the Mossad.

During this period, the US Embassy in Iran had been the centre of the news since 4 November 1979, when pro-Khomeini demonstrations turned protests into a siege of the embassy itself. What ensued, now referred to as the “Iran Hostage Crisis”, did not end for 444 days, finally finishing on 20 January 1981.

The US Embassy hostage situation in Tehran had made public diplomatic options between Iran and America limited. On 7 December 1979, J. Stanley Pottinger wrote to Warren Christopher, who was then Deputy Secretary of State. The letter was on behalf of Cyrus Hashemi, Pottinger’s client at the time, and contained a memorandum from Hashemi, which stated the issues he believed Iran was most concerned about. The letter also suggested that Hashemi was in frequent contact with various important players within the Iranian government and that he would be happy to become a conduit to help end the crisis via secretive diplomacy.

Hashemi had been busy; he had also made contact with Ramsey Clark, who was a former Attorney General and was teaching courses at Howard University School of Law, as well as being an associate of the New York law firm, Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. Hashemi had told Clark that he was hopeful of arranging a meeting between Khomeini’s nephew and a US representative. Ramsey Clark informed Harold Saunders, who was heading up the Iran Working Group (IWG), which had been set up by the State Department specifically to monitor the situation.

On the 12 December 1979, Saunders met Hashemi in Pottinger’s office where the Iranian recommended that the US develop channels of communication with people such as himself, claiming he had no particular political ambition, while also suggesting that the US representative chosen could also meet with Ayatollah Passendideh; Admiral Mandani, who was a high ranking member of Iran’s armed forces; or an Iranian economist named Dr. Mahmoud Moini. Hashemi pushed his agenda, but the IWG soon concluded that the Hashemis may be serving their own personal interests, noting that Hashemi might be seeking to avoid lawsuits. As Cyrus Hashemi’s proposals worked their way up the political food chain, there was still much scepticism. However, the Secretary of State at the time, under Jimmy Carter, Cyrus Vance, shelved his own doubts and recommended “secret exploration” of Hashemi’s proposals.

On January 2 1980, Saunders again met with Pottinger and Hashemi, but this time Dr Moini was present as a representative of Khomeini’s nephew. Alongside them was Cyrus Hashemi’s step-brother, Mohammad Ali Balamian Hashemi (commonly referred to as Jamshid but who also used various false identities, which included being called Abdula Hashemi, Jamshid Khalaj, and Jamshid Parsa). Jamshid Hashemi offered to establish a direct line of contact to Ayatollahs Pasendideh and Khomeini to help resolve the hostage crisis.

The Hashemis, along with Saunders, soon met with the chief of the CIA’s Near East Division, Charles Cogan, on 5 January 1980. At this meeting, the Hashemi brothers also claimed to be representing Admiral Ahmed Mandani, who was running for President of Iran. Jamshid Hashemi explained that he was “fully mandated by Mandani” to seek election campaign funds from the Americans. The Hashemis were offering something which the CIA craved: access to a potential future leader of Iran, Admiral Mandani, and the agency saw the Hashemi brothers as the key to forging this secret alliance.

As often happens with the CIA, what began as diplomatic channels opened to resolve a crisis soon became a potential opportunity to enact an American-aligned military coup. Hashemi promised Cogan that if the Passendideh mediation efforts resulted in failure, and if Mandani was not elected president, the hostages would be freed by the military action Mandani would take to overthrow the current regime. Cogan gave the Hashemis $500,000, saying that there were “no strings attached,” but requested an accounting of how the funds were spent and stipulated that the hostages had to be returned unharmed. Cogan attempted to deliver the cash to them on 17 January 1980 at the same New York hotel in which their original meeting had been held. Still, the Hashemis refused to accept the cash and instead insisted on a wire transfer. The money was to be moved from a Swiss bank account to an account in London.

However, by 7 February 1980, CIA officials had determined that Jamshid Hashemi was a “trafficker in intelligence to whomever would buy it,” and was “dishonest and untrustworthy beyond belief.” They also accused Jamshid Hashemi of exaggerating his contacts with Mandani and accused both the Hashemi brothers of withholding 90% of the funds intended for the presidential campaign. The CIA demanded that the brothers give a full accounting of how the funds were used and terminated their relationship. Madani lost the election, and Cogan estimated that $100,000 had been used for the operation. The Hashemis returned $290,000 of the funds in the form of a check, which they delivered to the private offices in Washington of J. Stanley Pottinger.

By late February 1980, the CIA had completely cut off contact with the Hashemis, but their investigations had also uncovered substantial information about fraudulent business dealings by the brothers. Even though the CIA had concluded that the Hashemis were unreliable, mainly due to the behaviour of Jamshid Hashemi, his brother Cyrus was not intending to give up. In late February, Cyrus Hashemi reported to the State Department that Reza Passendideh was to meet with him and Pottinger in Europe. Saunders briefed Pottinger with “just enough to give him some innocent but cogent questions”, which could help determine whether or not a meeting with Passendideh would truly be beneficial. The meeting eventually happened in Madrid on 2 July 1980, with Hashemi, Passendideh, Moini, and Pottinger gathering at the Hilton Hotel. Passendideh told them he was there because key people around Khomeini wanted to end the crisis.

The Office of the Historian holds many documents concerning the Iranian Hostage Crisis. One of them, entitled: “310. Memorandum From Secretary of State Muskie to President Carter,” which is dated Wednesday, 3 July 1980, states:

“We have just received a report of a meeting yesterday in Madrid between Khomeini’s nephew, Reza Pasandideh, (the son of Khomeini’s older brother) and Washington attorney Stan Pottinger. The meeting was arranged at Pasandideh’s request. According to Pottinger, Pasandideh claimed to be acting as Bani-Sadr’s emissary. He stated that Bani-Sadr was now interested in beginning talks in Europe between his representative and a U.S. representative, to discuss a possible settlement, including release of the hostages.”

However, it appears that the negotiations in Madrid were not perceived by the Iranians present as involving representatives of the sitting US President, Jimmy Carter; instead, Passendideh eventually told Abolhassan Bani-Sadr that he was meeting “Mr Reagan’s envoys.” Bin-Sadr later gave testimony to the “October Surprise Task Force” about the affair, which went on to be recorded in 1993 during the so-called ‘Joint Report of the Task Force to Investigate Certain Allegations Concerning the Holding of American Hostages by Iran in 1980’:

“Q: Well, did Mr. Passindideh tell you, Mr. President, who he had met?

A: So I said “who are these Americans?” And he said it was Mr. Reagan’s envoys.

Q: So, Mr. Passindideh believed that the people that he was meeting were people that Reagan had sent?

A: Yes, quite. Because he told me that if the “deal is not made with you then they’ll make a deal with your rivals.” And with Mr. Carter they were already in contact. They had three different channels of communication with President Carter. Those two French lawyers, the Swiss Ambassador, the German Ambassador. So it wasn’t worth talking about that with Mr. Passendideh.

Q: So your, just for the sake of summarizing so that I clearly understand it. Mr. Carter has three channels open through you. Mr. Passindideh, at Mr. Khomeini’s behest, meets with two people in Madrid, Mr. Hashemi and Mr. Pottinger. You believe that when Mr. Passindideh met with them, all they did was discuss negotiations on behalf or Mr. Reagan and not Mr. Carter, is that right?

A: Uh huh.”

It appeared that Pottinger wasn’t really concerned for the best interests of the US hostages being held at the Iranian Embassy. Still, it was instead playing a complex political game on behalf of his beloved Republican Party, and it shouldn’t be a surprise. Reagan was running alongside Pottinger’s good friend, George H. W. Bush, and, as we have already seen in the case of Orlando Letelier, Pottinger was willing to bend or break the rules to help Bush. Pottinger also still harboured some political ambition during this period and may have also coveted a position in the Reagan administration if he could help make this operation a success.

When the 1993 October Surprise Task Force needed to understand and track the meetings which happened during July 1980, Stanley Pottinger was happy to supply them with his telephone records and confidential attorney time-sheets. Pottinger’s client/attorney confidentiality, as far as Cyrus Hashemi was concerned, was no longer an issue, as by 1993, Hashemi had already died in London seven years prior after becoming ill with a rare and virulent form of acute myeloblastic leukaemia, which had been diagnosed only two days before his death.

In fact, there was more than one secretive rendezvous in Madrid during July and August 1980 concerning the Iranian Hostage Crisis involving some of the most prominent players of the era. Ari Ben-Menashe, a former Israeli intelligence operator, testified to having knowledge of four meetings in Spain in 1980 between William Casey, who was Reagan’s campaign manager at the time and later became the head of the CIA in January 1981, and Mehdi Karrubi, a prominent figure in the Islamic Republican Party.

Ben-Menashe went on to state that three of the meetings took place in Madrid and the last of them was held in Barcelona. Of these meetings, the first two were said to have taken place between February and May, with the third one at the end of July and the final meeting in August. The claim that William Casey went to Madrid at the end of July was disputed afterwards, as mentioned in Whitney Webb’s One Nation Under Blackmail Volume 1, which states:

“According to Jamshid, Casey, flanked by Donald Gregg and an unidentified man, attended two days of meetings with himself, his brother Cyrus, and Iranian officials in Madrid in late July concerning the hostages. Much of the debate relating to the October Surprise Task Force revolved around Casey having been in London for a World War II historical conference on the days when he was alleged to have been in Madrid. The Task Force noted that there were significant ambiguities in the conference attendance records, making it hard to know whether Casey could be consistently accounted for in London. Madrid is only an hour and a half from London by plane, conceivably giving Casey enough time to move between the cities in a relatively insignificant amount of time. While the media soundly rejected the possibility that this occurred, a State department cable later emerged from this precise time period stating that Casey had indeed been in Madrid for “purposes unknown.””

Webb also points out that there was more than just one Reagan campaign grandee staying in the same hotel as Jamshid, stating:

“There was another name that appeared in the guest records, right alongside the probable aliases of Jamshid Hashemi. On July 23, a “Robert Gray” checked into the Hotel Ritz, and on July 25 he checked out. Was “Robert Gray” actually Robert Keith Gray? Speculation swirled in the media, as Gray – at the time – was working on Reagan’s campaign directly under Casey.”

By 18 September, Saunders advised the Iran Working Group that Pottinger had contacted him to inform him that Cyrus Hashemi had been offered a special position by Rafsanjani, the Speaker of the Majlis, who wanted him to be one of two advisors to the Special Parliamentary Commission, which was considering the hostage crisis. A week later, Saunders again reported on Pottinger and Hashemi, saying that they were trying to work Hashemi back into the negotiation process by offering to track the Shah’s assets.

However, Cyrus Hashemi was also committing other, more serious actions behind the scenes. In September 1980, the US government received information from one of Hashemi’s former employees that they were actually helping the Khomeini regime to circumvent the United States arms embargo and sanctions, which had been levelled against Iran. That information came alongside an accusation that the Hashemis were circulating pro-Khomeini propaganda in the US. Saunders again brought in the CIA. By early October 1980, the CIA had uncovered substantial information concerning the business dealings of the Hashemis.

In the same year that Pottinger had helped to manufacture the October Surprise and, by doing so, helped to subvert the US democratic process, he was also defending Gerald Bull. Bull had similarly broken another arms embargo by selling weapons to South Africa, and you may imagine that Pottinger had the good sense to reject this later proposal by Hashemi. However, on 10 December 1980, Pottinger organised with Cyrus Hashemi and his brother Reza Hashemi to ship arms through a Netherlands Antilles trading company and to list the destination to a firm in Switzerland. The meetings took place in Hashemi’s New York office, which was under secret surveillance by law enforcement.

But Cyrus Hashemi and Stanley Pottinger were not the only people involved in US-Iran arms deals during this period. In fact, two very close associates of Cyrus Hashemi were also involved in the conspiracy to run arms as part of the Iran-Contra affair. The so-called “Saudi Arabian businessman” Adnan Khashoggi and an Iranian called Manucher Ghorbanifar were also both employed as conduits for the US-sanctioned arms sales to Iran. In fact, at the same time that Adnan Khashoggi was working with the National Security Council as a middleman for these illegal arms deals, a government informant, along with federal agents, was involved in a sting operation targeting the Saudis. On 21 December 1986, Robert E. Kessler wrote an article for Newsday which reported this failed operation to ensnare Adnan Khashoggi:

“The unsuccessful attempt to ensnare Khashoggi, which is mentioned in a conversation between Hashemi and a former lawyer for Khashoggi that was recorded by U.S. Customs Service agents on Jan. 17, 1986, seems bizarre enough in retrospect. “Obviously, they weren’t told everything that was going on,” said a ranking Justice Department official, referring to the agents and federal prosecutors who were working on the sting.”

The Kessler article also alludes to Pottinger’s role in the affair, stating:

“The story includes a 1980 offer to free the U.S. hostages in Iran that backfired, an investigation by the FBI and the Customs Service of a former Justice Department official who had been instrumental in investigating FBI agents for misconduct, the disappearance of a key wiretap tape, the recent demotion of the federal agent who lost the tape, and the death of Hashemi in what, some defense attorneys say, were mysterious circumstances.”

Kessler reveals that the secretive Foreign Intelligence Service based in Washington had authorised the 1980 wiretaps, which initially drew officials to the involvement of Pottinger himself. The wiretap had been placed on his telephones at the investment bank, which Cyrus Hashemi owned, First Gulf Bank and Trust at 9W. 57th St. and revealed that Hashemi had eventually become a government informant to avoid prosecution.

Hashemi and Khashoggi had worked together before their joint arms smuggling ventures. The aforementioned Newsday article also notes that:

“He [Hashemi] had represented the Iranian state oil company in London and had been a partner of Khashoggi’s and Furmark’s in an unsuccessful attempt early in 1985 to supply arms and other goods to Iran. But Hashemi and Khashoggi split before Khashoggi went on to serve as a middleman in the U.S.-sanctioned arms deal, some sources said. Hashemi also knew Ghorbanifar, whom he introduced to Khashoggi.”

Even though the article initially only alludes to a former Justice Department official’s involvement in the affair, Kessler eventually names Pottinger. The article reads:

“When Pottinger was in the Justice Department, he was instrumental in seeking to indict about 60 FBI agents for illegal break-ins at the homes of friends and relatives of alleged members of the Weather Underground in the New York area. He also was the boyfriend of feminist Gloria Steinem. Cases were eventually brought against only two ranking FBI officials in connection with the break-ins. The two were tried and convicted but were pardoned by President Ronald Reagan. In 1980, sources familiar with Pottinger’s role said he was not only Hashemi’s lawyer but also a business associate, having invested $100,000 in a merchant bank Hashemi was starting in London.”

While J. Stanley Pottinger was representing Cyrus Hashemi in 1980; Adnan Khashoggi was also being taken on as a client by other big players with strong intelligence agency connections. As reported in Whitney Webb’s One Nation Under Blackmail:

“Cohn and Gray reportedly knew each other, but the exact nature of their relationship is difficult to discern. They were, however, most certainly intimately acquainted during Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign, when both men worked closely with William Casey, who was the campaign’s manager and subsequently Reagan’s CIA director. Shortly after the campaign, Cohn, Gray and Jeffrey Epstein would all take on arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi as a client at the dawn of the Iran-Contra affair.”

In fact, J. Stanley Pottinger, one of the lead lawyers now representing many of the victims of Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell, organised a significant part of the Iran-Contra affair and benefited from the illegal sales of weapons, alongside Cyrus Hashemi, Adnan Khashoggi and Jeffrey Epstein himself. It is also during this period that Stanley Pottinger, later, admits to first working with Jeffrey Epstein, but that will be covered in the third part of this series.

By 1980, J. Stanley Pottinger had clearly become a high-level intelligence operative working in partnership with the CIA, dealing with some of the most sensitive issues of the day. But Stanley Pottinger wasn’t only living like James Bond professionally speaking, he even had his own “Pussy Galore.”

In 1974, while Pottinger was responsible for the official investigation into the FBI’s illegal surveillance and harassment of Martin Luther King Jr., as well as the Kent State massacre, he reached out to one of the leading feminist voices of the era. As well as the investigations into potential state-sponsored murder, Pottinger was also responsible for sexual discrimination charges, “which is how we met,” Gloria Steinem told Newsday’s David Behrems in the 12 March 1979 edition of the Boston Globe, in a piece entitled: “Steinem at 45… on life, love, self.”

However, there is much Gloria Steinem hasn’t told anyone before, and this investigation will not only look at the more widely reported links Pottinger’s long-term girlfriend had to the CIA, but also we’ll look at another event which happened while Gloria Steinem was being recruited by the Central Intelligence Agency in 1958, which has been almost completely wiped from history.

How “The Man” Disguised Himself as a Feminist Icon

Steinem was born to Leo and Ruth Steinem and was raised in Toledo, Ohio, from the age of 10 until 17. Her father ran a resort in Michigan during the summer months and was described by Gloria herself as “in show business of a sort.” Eventually, Steinem’s high grades saw her win a scholarship to Smith College, where she received her Bachelor of Arts degree in May 1956.

It is here that there are notable discrepancies in the official narrative. It was widely reported that Gloria Steinem had been awarded the Chester Bowles Scholarship upon graduating from Smith College, which was a two-year scholarship to travel around India beginning in 1956. Steinem seemed to be where the action was, wherever she roamed during these years, including riots in Ramnad and revolution in Rangoon. Still, she also famously befriended Indira Gandhi and the widow of the “revolutionary humanist” Narendra Nath Roy. It is also during this time that Gloria Steinem appears to have been surreptitiously recruited to the CIA, via an agent she met in Delhi named Clive S. Gray… who we’ll talk about shortly.

After her tour of India ended, Steinem was to be instrumental in organising an anti-communist operation at a festival in Vienna for the CIA. However, during the brief period of time between Steinem being recruited by the CIA in India and organising the CIA-led effort in Austria, there is another, much more sinister and little-reported event with which the freshly recruited CIA operative, Gloria Steinem, was involved. That event saw Steinem become a key witness and narrative setter in the very suspicious and mysterious death of a high-ranking US Navy officer in the Pacific Ocean.

On 25 July 1958, the Daily Times newspaper of Ohio was one of the many outlets to run the syndicated news article on the very peculiar disappearance in a piece entitled, ‘Transferred Admiral Lost At Sea; Suicide Suspected.’ Rear Admiral Lynne C. Quiggle had been in the process of transferring from his post as Deputy Chief of Staff on the Joint Staff Command of US Forces in Japan, where he had also been assigned as the United States Forces’ Japan representative to the US-Japan joint committee, which had been set up under an administrative agreement between the two countries.

Quiggle had been on board the President Cleveland, a steam passenger ship initially constructed for battle during WWII but refitted to be a steamliner by 1947. The Cleveland had been taking Quiggle and his wife en route to his new base in San Diego, California, where he’d assume command of Amphibious Group 1 of the Pacific Fleet. During WWII, he served on the Iowa battleship, which was used to transport Franklin D. Roosevelt to an Allied conference in Tehran. With a prestigious career under his belt, Quiggle was seen as a veritable war hero. A few years before Quiggle’s untimely demise, he had also been appointed to the UN Military Armistice Commission in Seoul.

By 24 July 1958, it was being reported that Lynne Quiggle had probably committed suicide by jumping overboard around 800 miles off the US coast. Remarkably, in two of the syndicated news reports which were published across America following Quiggle’s death, Gloria Steinem is quoted as a key witness. In the aforementioned Daily Times article, it states:

“Fellow passengers said Quiggle had been acting peculiarly. One, Gloria Steinem, 24, of Washington, DC, said a ship officer told her Quiggle was heard to say to his wife: “You are better off as a widow.” “The admiral then kissed his wife and walked slowly from their stateroom,” Miss Steinem said.”

The quote from Gloria Steinem wrapped a proverbial bow over the suicide theory, although his family later argued that suicide was very unlikely. In fact, on 8 August 1958, Rear Admiral Lynne C. Quiggle’s brother was reported as stating that “there was no justification for calling it a case of suicide.” At the time of Quiggle’s disappearance, the man in charge of the President Cleveland, Commodore H. D. Ehman, had been quoted as stating: “There was no indication at all of any foul play,” going on to say:

“The last I could establish that anyone had seen him was a steward who had seen him go out on the deck from the lobby about 4:45 A.M. I felt very little could be accomplished by turning the ship about.”

Lynne Quiggle’s supposed last words were repeated in various newspapers over the following weeks, words first reported by Gloria Steinem, a 24-year-old student who was in the process of being recruited by the CIA. The Miami Herald also quoted Gloria Steinem in an article on 25 July 1958, but on this occasion, the article gives more detail:

“Miss Gloria Steinem, 24, Washington D. C., a student who became friendly with the Quiggles, said she was told by one of the ship’s officers that Quiggle was heard to tell his wife. “You are better off a widow.” This was after midnight Tuesday, she said. The officer told her the admiral then kissed his wife and walked slowly from their stateroom.”

Lynne Quiggle’s wife was reported to be in a state of shock and unable to answer any questions, leaving Gloria Steinem, a fresh-faced, newly recruited member of the CIA, to talk to the press and convey her husband’s supposed final conversation to the world. What’s most astonishing is that on 11 August 1958, about 18 days after the tragic disappearance of Lynne C. Quiggle, the Hanford Sentinel published an article entitled, ‘Disappearance of Rear Admiral From Aboard Ship Still Mystery’ and afterwards there are no more mentions of Quiggle. It is almost as though the case was abandoned entirely, with Doyle Quiggle, brother of the deceased, stating:

“The skipper classified it as suicide. But he was in no position to know. The Navy Review Board, which began it’s investigation as soon as the ship docked, did not produce any evidence of suicide.”

Lynne Quiggle’s brother argued vehemently against the theory that his sibling had committed suicide, stating that there “was nothing in his character to justify such a conclusion.”

Whatever the truth, a compelling narrative had been created by Gloria Steinem. Whether Quiggle’s wife had actually reported his supposed last words, or whether it was unreliable second-hand information from a globe-trotting student who had been recently recruited by the CIA, the true circumstances surrounding Quiggle’s death were never cleared up, and the case soon vanished from the public eye.

Steinem talks about this period of her life, and even briefly mentions befriending the Quiggles, in a book by Sydney Ledensohn Stern written in 1997 entitled Gloria Steinem: Her Passions, Politics and Mystique. The book states:

“Gloria explains. Not only did the crew speak English, they sneaked her above decks during the day so she could mingle with the more privileged passengers. Among them were Rear Admiral and Mrs. Quiggle, and when Admiral Quiggle disappeared en route, the tragedy was the talk of the ship — especially since one of the ship’s officers had overheard the admiral tell his wife, “You’d be better off a widow.” When they docked, the captain forbade the crew to speak to the press about the incident, but Gloria had received no such instructions, so she tried to be helpful. She answered reporters’ questions and was shocked to find herself quoted from Washington to Tokyo.”

In 1959, the so-called ‘Independent Service for Information’ (ISI) was set up at Harvard, coincidentally while Pottinger was a student at the university. The program was created to target European youth attending the Vienna Youth Festival, with anti-communist propaganda designed, supplied and delivered secretly by the CIA. To achieve this goal, the agency required the participation of youth leaders who were well-travelled and capable of persuading young people that communism was the enemy.

Steinem is even mentioned in Hugh Wilford’s critically important historical masterpiece, The Mighty Wurlitzer, which covers the creation of the CIA and much of its early leadership and development. In a chapter entitled ‘Students’, Wilford writes:

“It was the fall of 1958 and, like many educated young women of her generation, Gloria Steinem was having difficulty finding a rewarding job. Dazzlingly bright and talented, just returned from a year-and-a-half-long scholarship trip to India, where she had befriended Indira Gandhi and the widow of revolutionary humanist M. N. Roy, the twenty-four-year-old Smith graduate was reduced to sleeping on the floors of friends’ apartments as she hunted for work in New York. Then came a call from Clive S. Gray, a young man she had met in Delhi, where he was ostensibly working on a doctoral dissertation about the Indian higher education system.”

Steinem met Gray and another CIA agent called Harry Lunn in New York to discuss the Vienna proposal. Lunn had previously been a former National Student Association (NSA) president and, according to Wilford, fell in love with Steinem. Afterwards, Steinem was sent to Cambridge, Mass., to meet with Len Bebchick and Paul E. Sigmund Jr., both former NSA Vice-Presidents for International Affairs, who were accompanied at the meeting by a Boston lawyer named George Abrams.

In January 1959, Gloria Steinem took up the post of Director of the Independent Services for Information located on Harvard Yard. The CIA front organisation supplied her with a handsome salary of $100 a week – equivalent to over $1000 a week in today’s currency – an extra $5 to help towards the expensive rents in Cambridge, as well as being paid a general allowance which was to be decided by the infatuated Harry Lunn. When discussing what the ISI wanted to achieve, Wilford goes on to write:

“The ISI was a CIA operation from beginning to end. Spectacularly staged festivals celebrating the themes of international peace and friendship were a crucial element in the communist campaign to capture young hearts and minds: witness the success of the 1951 Berlin rally, which had helped concentrate CIA minds on student affairs. The fact that the Vienna World Festival of Youth and Students was being planned personally by the new head of the KGB, former student leader Alexander Sheljepin, was some measure of the importance it was accorded in the Kremlin.”

Not only was it clear that the ISI was a CIA operation, Steinem soon discovered this fact for herself after asking about the funding for the project, with Wilford writing:

“Lunn, Sigmund, and Bebchick were all working directly for the CIA when they organized the ISI. So too was Gray, whose real purpose in India was talent-spotting potential agents in the student movement. As for Steinem herself, she became witting when she began asking questions about the ISI’s funding, and the undercover CIA officers explained that the Boston grandees and foundations apparently subsidizing the venture were in fact pass-throughs for secret official funds.”

Who is J. Stanley Pottinger?

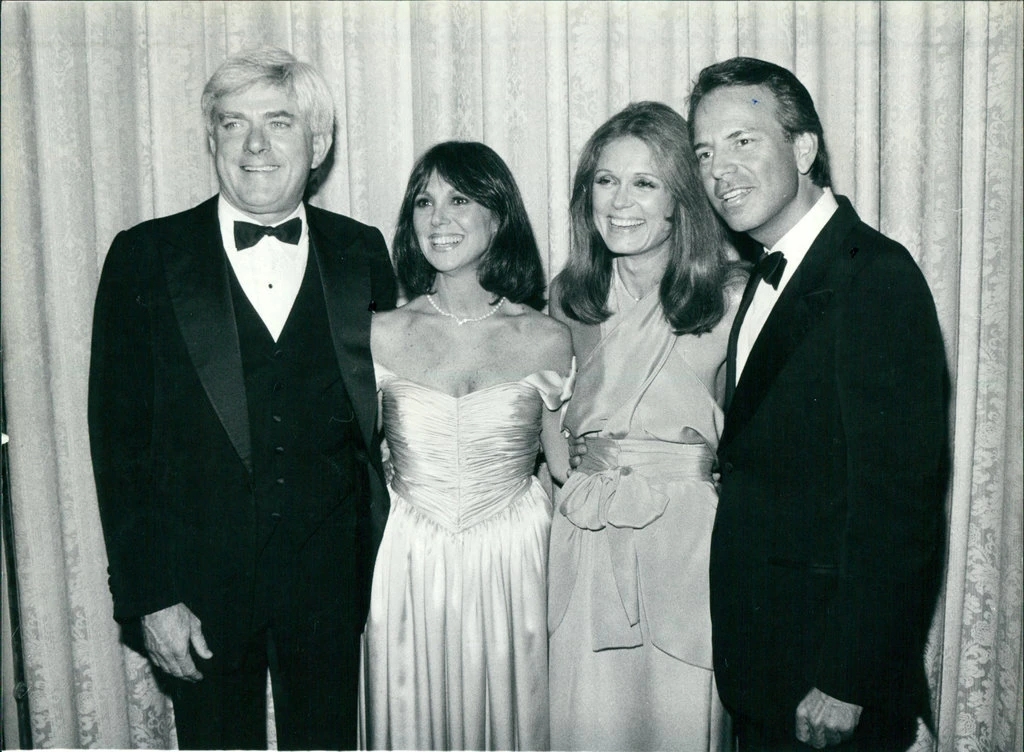

By 1983, Steinem and Pottinger’s relationship was almost a decade old, and they were still seen out together regularly. In December that year, the couple appeared on ABC’s “20/20” program dancing together, with Steinem also showing off her tap-dancing ability to the host, society favourite Barbara Walters. Even though Steinem was more open about her relationship with Pottinger as the 1980s began, she had initially tried to keep her love life under wraps.

In 1972, a couple of years before Pottinger and Steinem say they first met, she co-founded ‘Ms.’ magazine and became one of the most visible feminist leaders in the US. For her, admitting she was dating a Nixon-era grey-suited company man was clearly not something she felt she needed to do. In fact, Gloria Steinem had carefully constructed her image to become a prominent and influential figure, targeting young American girls. In 1978, Steinem was living with Pottinger and finally opened up to the press about her long-time lover, with the Times-Post News Service reporting on 10 March 1979:

“Pottinger, 39, former head of the Justice Department’s civil rights division, is now in private practice, specializing in civil rights cases. “They’re cases in which some principle is at stake, so there’s some satisfaction,” Steinem said. In the mid-1970s, Pottinger headed the department’s probe into the FBI and Kent State crisis. He was also responsible for investigating sex discrimination charges – “which is how we met,” Steinem said.”

However much colour Steinem applied in an attempt to paint Pottinger as a noble character, in reality Pottinger’s clients after leaving his position in the justice department included: Chemical Bank; Mead, Gerald Bull and the Space Research Corporation, not to mention the Hashemis, which led to his involvement in Iran-Contra. The claim that Pottinger was still working primarily on civil rights issues during this period was one of the many lies Steinem told to retain her own manipulated public image that had been manufactured by herself and the Central Intelligence Agency. Although many people looking on were wondering about potential future wedding bells, it was also reported that Steinem herself was categorical in saying that the relationship would never lead to marriage.

In 1982, Steinem and Pottinger were again reported mixing with the elites, this time attending a party on the Queen Elizabeth II (QE2) organised and hosted by Georgiana Bronfman and her husband, the chairman of Joseph E. Seagram and Sons Inc., Edgar M. Bronfman. The party saw over 1000 of the wealthiest and most powerful people gather to raise $108,000 in funds for the Wolf Trap Foundation and the Upward Fund. The Bronfmans had footed the bill for the gathering, which cost $100,000, almost as much as the total funds raised. On that occasion, Pottinger and Steinem also brought a guest along, a New York Times article from 18 January 1982 stated:

“Avoiding the press, Mary Cunningham, now a Seagram vice president, came with William M. Agee, the chairman of Bendix, where Miss Cunningham once worked. Gloria Steinem, in burgundy velvet and an Indian-style gold headband, chatted with George J. Green, the president of The New Yorker, both guests of J. Stanley Pottinger, a Washington civil rights lawyer.”

Steinem and Pottinger were together for a decade before Pottinger’s involvement in the Iran-Contra affair started to emerge in 1984. In March that year, they were still noted as arriving at an event together, that event being the 50th birthday of Gloria Steinem, which took place in the Grand Ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria, but after the FBI publicly outted Pottinger as instrumental in the sale of illegal weapons during the Iran-Contra affair, Steinem and Pottinger’s own affair soon comes to an end. Whether it was all of the attention stirred up by Pottinger’s central role in the Iran-Contra scandal, or whether the decade-long relationship had just petered out naturally, Steinem and Pottinger were soon to find new lovers within the Establishment, with Pottinger beginning a relationship with Kathy Lee Gifford and Steinem leaving Pottinger’s embrace for that of billionaire industrialist Mort Zuckerman.

Kathie Lee Gifford – who was still Kathie Lee Johnson when they began dating – was the ravishing co-host of WABC-TV’s Morning Show alongside Regis Philbin. In a Daily News article dated 29 December 1985, her new relationship with Pottinger is discussed, stating:

“She’s got a date for sushi with the man in her life for the past year and a half, Stan Pottinger. She met Pottinger, 45, an assistant attorney general during the Nixon and Ford administrations, when he was still involved with feminist Gloria Steinem. “He remembered saying to himself, ‘I’ll call her someday,’” reveals Johnson. “I’m more in love right now than I’ve ever been,” she says. “He’s the smartest man I’ve ever known. The funniest, too. He’s the first man I’ve been with who’s completely secure in himself.” Will they get married? “Marriage scares us both,” she confides.”

However much Kathie Lee Gifford was in love, J. Stanley Pottinger was not a man who looked to settle down. By November 1992, Kathie Lee Gifford’s career had been a success, and Pottinger was just a sad memory. Talking to the Daily News, Gifford admitted how she began to lose her own religious identity during their relationship, saying:

“I became one of the least religious people you’ll ever meet, because I understood religion imprisons people, wants them to parrot the same slogans and conform.” She tried sex outside marriage – “had my teenage rebellion at age 30” – but fell into destructive relationships with boyfriends like Gloria Steinem’s ex-beau Stanley Pottinger – men who were emotionally unavailable. “I was still in an emotional rut myself, didn’t have my self-esteem, and dated men very similar to my first husband,” she says. “Stanley was a roller coaster – brought me to the heights of joy and the depths of despair.”

By 1984, the Iran-Contra affair had become public. Indictments followed, with five defendants named as part of the complicated case. Although Pottinger had been heavily involved in the illegal trade of arms with Iran, he was eventually only investigated and not indicted. On 19 July 1984, the New York Times quoted then US Attorney Rudolph W. Giuliani saying:

“The investigation of Mr. Pottinger is continuing, It would be unfair to make judgement at this point.”

J. Stanley Pottinger should have been in an awful lot of trouble, and even his own lawyer, T. Barry Kingham, stopped returning telephone calls for comment on the case, ignoring four from the New York Times alone. The public exposure of the Iran-Contra affair left Pottinger in a very tight spot. In fact, those who were reading the many news articles related to this breaking scandal during the mid-1980s weren’t privy to all the information, and it would be years before the events concerning the October Surprise were put under anything close to proper public scrutiny. Regardless, as the news broke, it was now public knowledge that Pottinger had been central to the illegal sales of arms to the Iranians, yet he wasn’t indicted.

In reality, the Iran-Contra affair was a complex series of events involving numerous covert actions that remain largely unknown. To avoid potential criminal prosecution and the various difficult questions which were being asked, Pottinger moved to Mexico for a while, at least until the dust settled. If Pottinger’s role in Iran Contra and the October Surprise were thoroughly investigated during this period, this would have undoubtedly led to further questions about his role in creating the official narratives around Watergate, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and the Kent State Massacre, not to mention his involvement in cases such as the stand-off at Wounded Knee, Orlando Letelier and his authorising of the CIA’s domestic surveillance of US citizens, as well as the Nixonian desegregation policies in general while Pottinger was the Director of the Office for Civil Rights.

J. Stanley Pottinger had gained public recognition throughout the 1970s, being the official face of an emerging and evolving section of the Justice Department. However, by the 1980s, Pottinger’s public face had almost completely vanished, only to be replaced with the shadowy features of an intelligence asset. By March 1989, The State newspaper of South Carolina was asking ‘Who is Stanley Pottinger?’ but without being able to give any real answers, as the true face of J. Stanley Pottinger will not be found in the public archives.

In the third instalment of The Road to the Takedown of Jeffrey Epstein, we will explore Pottinger’s life from 1990 onwards. The upcoming article will present previously unreported information. I’m expecting various people involved with the case to begin to fundamentally change parts of their stories as the information starts to be anticipated and revealed. The direction of this series is clear to those who have insider knowledge. At this point, anything could happen. Thanks for reading, and please support my work. Your support gives me breath, wakes me up, and helps me write.