By Johnny Vedmore via NEWSPASTE Originals – Read Part 1 Here

Stanley Setty is dead and buried but officially his murder is still unsolved. Brian Donald Hume had been sent to prison for disposing of Setty’s corpse while simultaneously being acquitted of his savage murder. However, Hume was planning his return to the limelight with a bold public confession to the murder of Stanley Setty and it was only a matter of time before the murderous Hume would strike again.

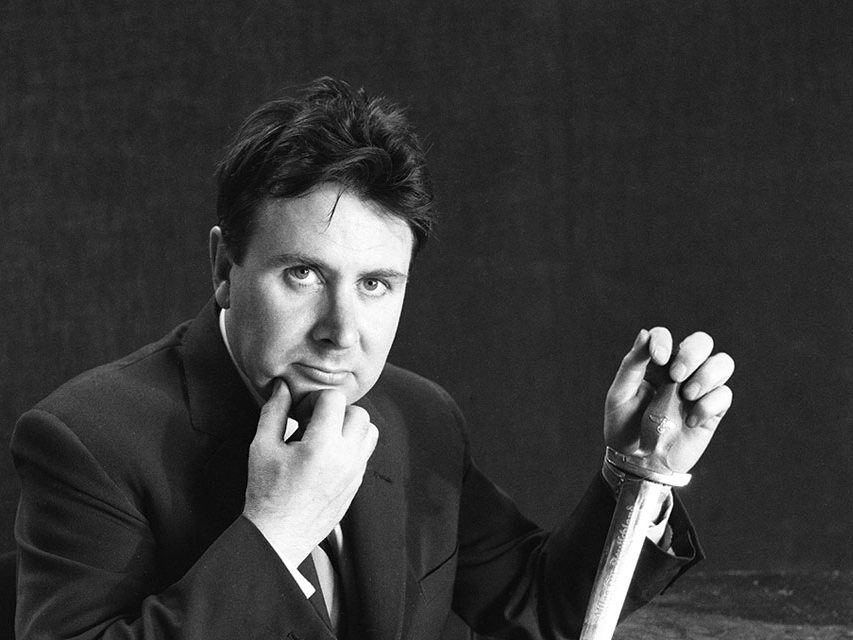

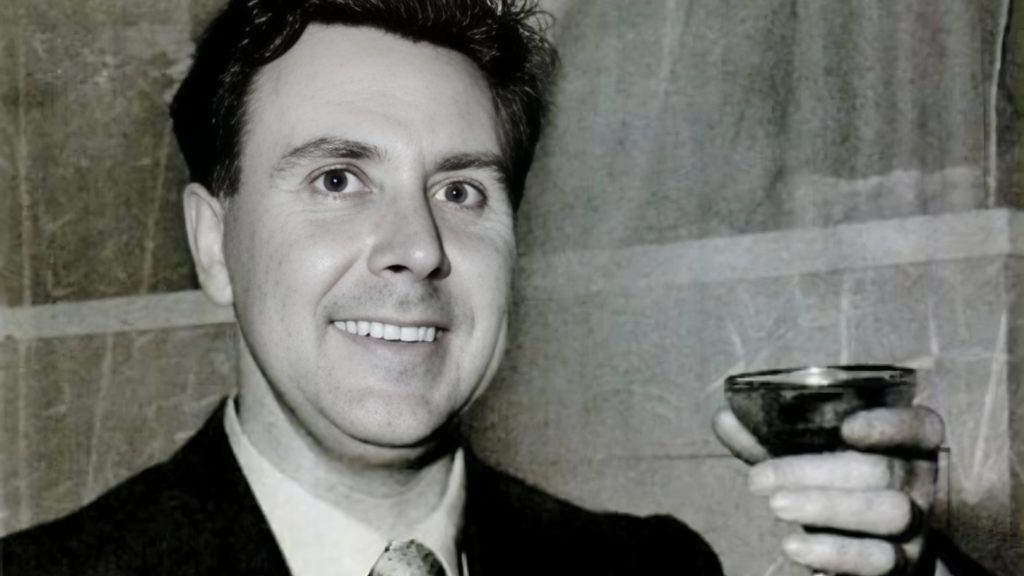

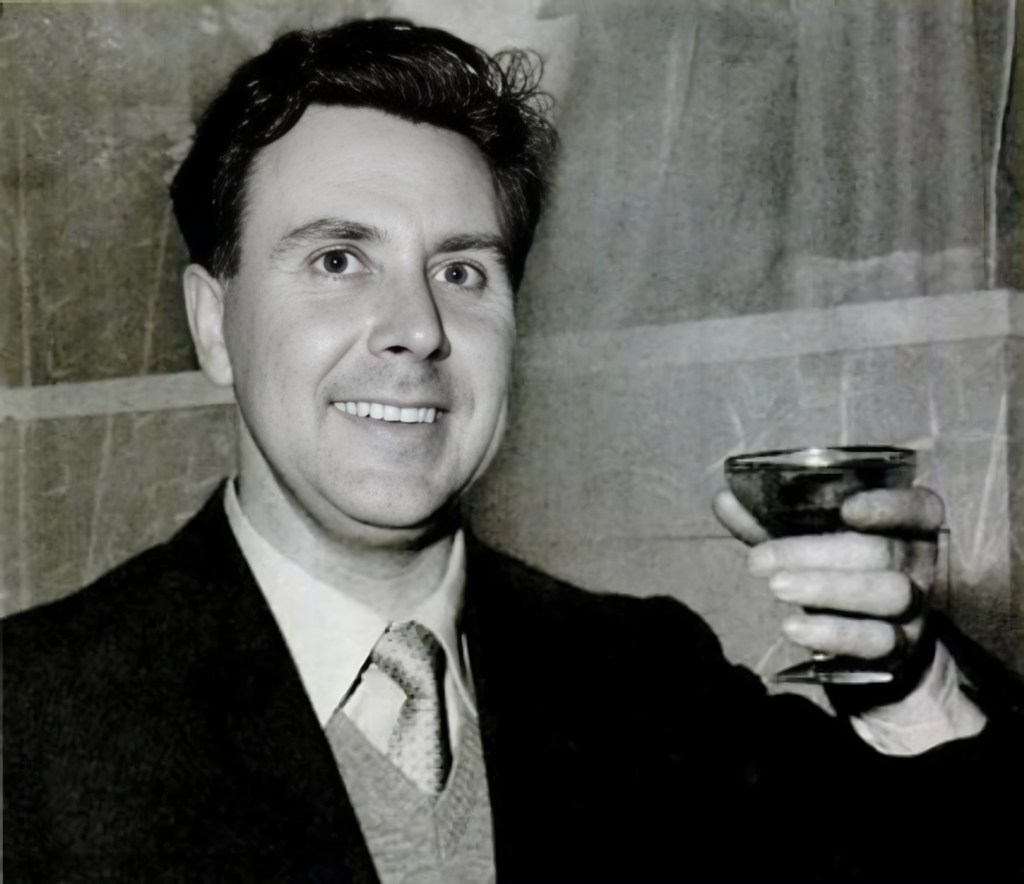

Brian Donald Hume had become akin to a superstar and he had kept himself busy by writing down his own story. Hume clearly harboured an abundance of bitterness and was eager to settle some personal business while he was still the centre of attention publicly. After he was placed in jail, interviews that Hume gave to the press became full to the brim with reasons why people should be sympathetic towards him.

Almost immediately after his conviction for disposing of Setty’s corpse, the Sunday Pictorial struck a deal with Hume to start telling his story under the headline, ‘The Astonishing Revelations of Hume’, saying:

“What has Hume got to tell? His is the story of an orphanage boy who could not forget his early hardships and frustrations. The illegitimate son of a schoolmistress, and nephew of one of Britain’s greatest scientists, he nursed a grievance against the world for denying him the opportunities he felt should have been his.”

The article goes on to explain that Hume had once become a member of the Communist Party in Great Britain and that he was drawn into London’s shadowy underworld after being invalided out of the RAF in 1941. The piece also reveals that Brian Hume had been planning to escape from Brixton Prison with a band of fellow prisoners who were being housed alongside him in the hospital wing of the prison.

The next edition of the Sunday Pictorial ran with another Fred Redman article on the front of the publication entitled: ““I Hate My Mother” Says Brian Hume.” Although Hume was obviously quite an angry person in general, his reported relationship with his mother had clearly been a negative influence on his life. The article explained that Hume’s mother was apparently a kindly schoolmistress who had given him up to an orphanage when he was very young. Years later, when Hume was seven or eight years old, he had been supposedly adopted by a caring stranger. The women he went to live with was in fact his real mother, yet she hid her true identity from him and told him to refer to her as ‘aunt.’ It was a year later that Hume was told by his step-sister and some villagers that his adopted mother was actually his birth mother.

Hume also spoke of another [see part 1] memory involving his mother and birds. He had found a bird with an injured wing and the young Hume wanted to nurse it back to health. The young boy took the poor creature home but his mother promptly killed the bird. This reoccurring theme of motherly rejection leading to the death of birds may have been warning signs which nobody had realised they should take notice of. The paper also reported more on his previous communist activities, which had included selling the Communist Party’s paper in Piccadilly and joining anti-rich demonstrations at West End hotels, with Redman stating: “And that’s why he became a crook.”

In fact, Brian Donald Hume was being encouraged to become a bit of a public sensation, spurred on by the endless tabloid coverage which sensationalised everything he was doing. Even relatively far flung papers such as the Calgary Herald were reporting on Hume, in articles where the journalists used inviting language such as “semi-honest’ and referring to him as “handsome in a heavy sort of way.” The constant stream of articles painted Hume as a sort of obscure everyman hero, but the truth was a lot more pathetic. Brian Donald Hume was a desperate attention seeker and the worst thing the society around him could have done was feed his need to be in the public eye. It seemed that the stories and images which Hume painted for people, captured their imaginations and evidently clouded their judgement. Hume himself had successfully seeded various fake narratives and imaginary characters into a court case which was meant to have seen justice for Stanley Setty and his loved ones. Hume projected a false image of himself to everyone who had been captivated by the case and who were paying close attention to his enthralling trial. It was Hume who said: “I am a semi-honest man, but I am not a murderer,” a statement which echoed throughout the many newspapers worldwide which were busy covering the case.

Publicly Hume had said a lot directly after the verdict and some of his blabbermouth behaviour saw Scotland Yard begin investigations into certain statements he had made after the close of his trial. This led to Superintendent Peter Beveridge and Chief Inspector John Jamieson attending a conference to give the press updates on the ongoing investigations into the case. The police had searched a garden in Kings Langley as the result of statements made by Hume, looking for a large number of £5 notes which had never been recovered. What were described in the newspapers as “Hume’s prison talks” were also reportedly about to lead to a charge of perjury for someone who was described in a Sunday Dispatch article from 19 February 1950 as having been ‘an important witness at Hume’s Old Bailey trial.”

Hume had said a lot publicly directly after the verdict and some of his blabbermouth behaviour saw Scotland Yard begin to investigate statements he had made at the close of his trial. This led to Superintendent Peter Beveridge and Chief Inspector John Jamieson attending a conference to give the press updates on their ongoing investigations. The police had searched a garden in Kings Langley as the result of statements made by Hume, reportedly looking for a large number of £5 notes which had never been recovered. What were described in the newspapers as “Hume’s prison talks” were also reportedly about to lead to a charge of perjury for someone who was described in a Sunday Dispatch article from 19 February 1950 as having been ‘an important witness at Hume’s Old Bailey trial.”

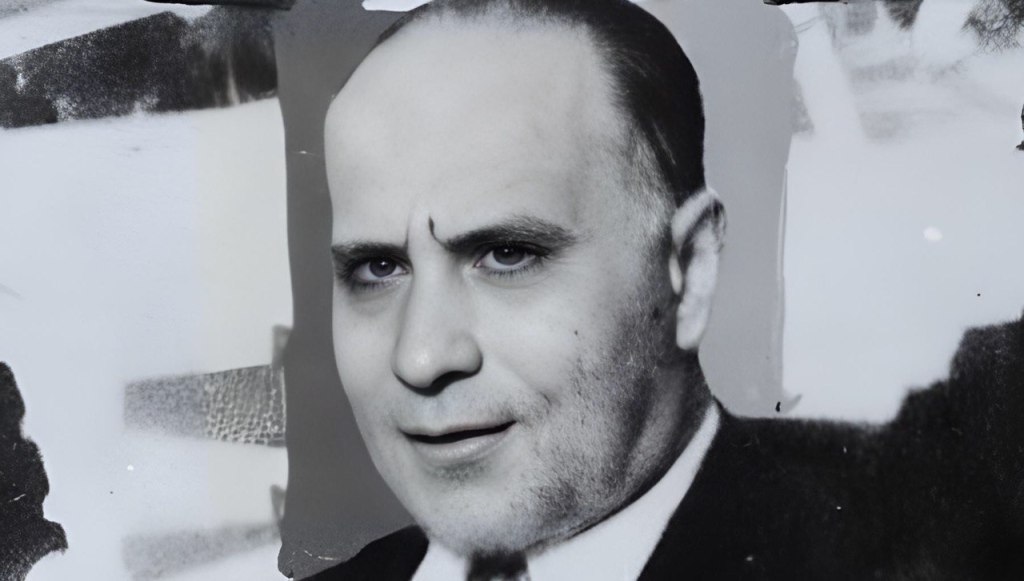

Hume was a magnet for intrigue and his ability to make the news didn’t end with his incarceration. Another prisoner interned at Wormwood Scrubs was a man named Dr. Klaus Fuchs who was referred to as an ‘atomic spy’. Fuchs had been convicted on 1 March 1950 for breaking the Official Secrets Act by “communicating information to a potential enemy.” In fact, Fuchs had helped the Soviet Union in their efforts to create an atom bomb while the British were still allied to the Russians.

In prison, Fuchs was quickly befriended by Hume and, on 4 June 1950, it was reported in the People newspaper that Brian Hume had successfully persuaded Fuch’s to report his ‘former-espionage associates’ to FBI investigators. The article which reported on the strange prison bedfellows stated:

“Fuchs, of course, could have refused to give any information. But Hume, who tried to do a bit of “shopping” after his own conviction – and incidentally caused the Yard considerable trouble investigating his imaginative stories – convinced the doctor that it would pay to co-operate with the FBI boys.”

By October 1950, Hume had requested to transfer from Wormwood Scrubs to Wakefield jail so he could pursue “intellectual and academic attainments” and other educational courses which were available at the northern prison. In April 1951, a housewife from Wolverhampton who claimed to have “visions” was reported to have “seen” Stanley Setty’s murder. Mrs. Zita Boydon said that she usually had her prophetic visions in the evening time just before dropping off to sleep. In the same month, Scotland Yard were asking for a pathologist report to be made on a human skull found half buried in sand at St. Osyth, near Clacton-on-Sea. The police were still on the look out for Stanley Setty’s skull as his head had never been recovered. By the 15 June 1951, Mrs. Cynthia Hume, the wife of Brian Hume, issued a divorce petition for the dissolution of their marriage.

By September 1951, Hume was making what were described as remarkable disclosures about the crime, again to the Sunday Pictorial reporters. Hume was making a major change to his statements in court. The article read:

“Setty, he [Hume] says, was murdered in Camden Town – not at Golders Green, as was thought at the time of the trial. His dead body was driven around London in a car.”

Brian Hume’s entire trial had revolved around the notion that Setty had been murdered in Hume’s flat, but even though Hume was publicly changing his statements, there appeared to be absolutely no will to pursue another conviction. It was clear that, while Hume was behind bars, the authorities remained apathetic towards the Setty case and were showing no interest in re-igniting an investigation, especially not one focused on Hume. Throughout the 1950’s, the Setty case came back into focus over and over again. In July 1953, detectives investigating the Rillington Place murders of Beryl Evans and her baby daughter, along with the involvement of serial killer and necrophiliac John Christie, examined pictures which had been taken of Setty’s remains. The police were not connecting the crimes to the Setty murders, but were instead looking to examine how the packages containing the bodies had been stitched in a similar fashion. The reason detectives were focused on this detail may have been due to Superintendent Peter Beveridge, who led the Setty case and who was also in charge of the Rillington Place murder investigation.

In 1956, another skull found in Essex was to be tested to see if it had belonged to Stanley Setty. By December 1957, it was being reported that Brian Donald Hume was due to leave prison early in February the following year. The Sydney Morning Herald reported that he was now being held at Dartmoor prison where his number was Prisoner #127. The newspaper was also reporting on more of Hume’s public bombast which had been unusual behaviour to see from a man about to walk free, stating that:

“Hume’s plan to reveal secrets of the Setty murder came in a dramatic message to a Christmas caller at Dartmoor. Hume whispered across the table: “The police were all wrong about the murder. I am going to tell it all when I get out.”

On the 31 January 1958, it was reported that Hume was to be freed the following day after serving eight years for being an accessory to murder after the fact. Almost as soon as he was released, Hume headed towards the limelight again, this time claiming to know more about the Rillington Place murders. Hume had served some of his time at Dartmoor prison alongside Timothy Evans and, whether or not Evans had confided in Hume, this connection was enough for the general public to speculate on. The following month, Hume was also claiming to know more about the Russian atomic bomb program based on information he claimed Dr. Klaus Fuchs gave him. Another unnamed man, described as “Mr. X” in the Albuquerque Tribune on 1 May 1958 claimed that Fuchs believed Hume was transferred from Wakefield to Dartmoor because their friendship worried security authorities.

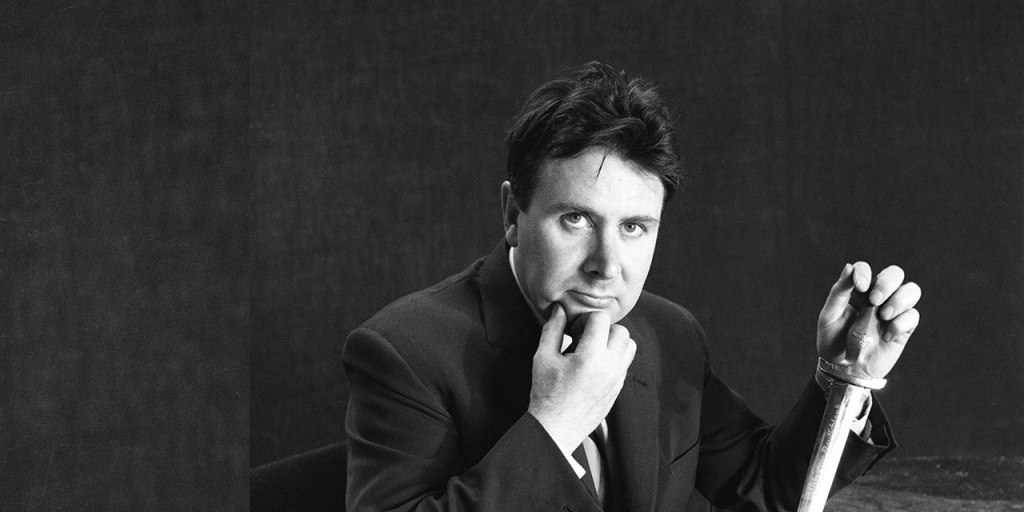

I Did Kill Stanley Setty

Within months of being released from Dartmoor prison, Brian Donald Hume had openly confessed to the murder of Stanley Setty. On 1 June 1958, the Sunday Pictorial finally got the big story which they had been trying to coax from Hume for over 8 years. The front page of the paper saw capitalised letters in large font read: “I Killed Setty… And Got Away With Murder”. Underneath the astonishing headline it was written:

“I, Donald Hume, do hereby confess to the Sunday Pictorial that on the night of October 4, 1949, I murdered Stanley Setty in my flat in Finchley Road, London. I stabbed him to death with a dagger while we were fighting.”

This was the first in a series of articles which were due to be released in three parts throughout June 1958. Below his front-page confession, on one of the best selling newspapers in the UK at that time, was Brian Donald Hume’s signature. Inside the Pictorial was a further headline boldly titling the piece, “My Murder.”

Hume again spends much of the first article in the series ruing the treatment he received when he was younger at the hands of his mother. He also explains how he pretended to be an RAF war hero with a uniform complete with ‘wings’ which one publication claims he bought for £5, while another says it cost Hume £14. This latter admission of pretending to have served in the RAF was also documented by others following the case. In October 1961, in an article in the Herald Express, the paper recalls a visit to Torquay Carnival by a young Brian Donald Hume. On that occasion, Hume had been staying in the nearby Grand Hotel where he had signed in as “Capt. D. B. Hulme,” and had claimed to be a Pan-American Airways pilot. Hume was tasked with driving the carnival queen around Torquay in what was termed the “carnival Cadillac”.

In the second article of Hume’s confession within the pages of the Sunday Pictorial, the paper covers Hume’s murder of Stanley Setty and the reasons behind it. Hume states:

“It was 7:35pm. I was livid with anger at this man for whom I had been earning money by stealing cars. The cars I stole on his order had to match the log-books of wrecked vehicles he had already bought. But, furious as I was, I did not know then that seventeen minutes later I would have his dead body – and his blood – on my hands. I began to tremble with rage when this black marketeer refused to get out. I saw red. I yelled at him, then ran out on to the landing and snatched a dagger from the collection of war souvenirs on the wall. The handle of the dagger glinted in the light. I could see the initials “S.S.” In war, they stood for Schutz Staffel, the elite army corps of Nazi Germany. Now those S.S. initials stood for forty-four-year-old Stanley Setty. I dashed, dagger in hand, through the doorway of my living-room and towards Setty. I planned to frighten the living daylights out of him, But I reckoned without myself – and my own rage. Back in the living room, I brandished the blade. Baghdad-born Setty’s dusky face seemed to whiten. His forehead looked shiny. For a moment he looked scared, but then he said: “Go away, you silly bastard. What do you think you are doing? Playing at soldiers?” I looked him straight in the eye. “I’m not playing,” I said earnestly. I took another step forward, the dagger still in my right hand. Setty sneered: “You can’t frighten me.” And then he took a swing at me with the flat of his hand. He towered above me, tall and powerful. We grappled. In a split second – it happened so quickly – we were rolling on the floor. I was wielding the dagger just like our savage ancestors wielded weapons 20.000 years ago. It seemed to come naturally to me.

We rolled over and over and my sweaty hand plunged the weapon frenziedly and repeatedly into his chests and legs. I had hurt him. I aimed my blows anywhere. But Setty continued to struggle. He was as strong as an ox. The more I stuck the dagger into him, the more he tried to push my head back and break my neck. I tried to push Setty away from me to keep the blood off my clothes and force a gap between us. I forced my knee into him. He grunted. But he wouldn’t release his grip. It was like a vice. I held the knife up to strike the sixth or seventh blow, I can’t remember. I plunged the blade into his ribs. I know, I heard them crack. He sank back against the sofa and slumped on the floor. He writhed and rolled over to a spot beneath the window, on his back. Setty began to cough violently and a trickle of red came from his mouth as he heaved and panted. I stood over him with the dagger in my hand. And, with a feeling of triumph at winning the fight, I watched the life run from him.”

And, just like that, Brian Donald Hume confessed publicly to the murder of Sulman “Stanley” Setty. Hume’s confession sent everyone involved with the case completely apoplectic but Hume had expected this to happen. By 1 June 1958, British legal authorities were facing a unique problem. The news was reported all over the world with even the Civil and Military Gazette of Lahore, India, asking:

“What are they [British legal authorities] to do about a man who has been acquitted of murder – and who later confesses that he was the murderer after all?”

For one of the first times in modern history, people were listening to a murderer who had got away with murder, explain in detail how he committed the crime and how he disposed of the body. After hearing this confession, the general public also knew that Brian Donald Hume was walking free somewhere in Britain.

The Daily Sketch publication demanded, in what was described as a ‘screaming banner-line,’: “Arrest this man!” But Hume had already made extravagant plans to escape any further attempts to apprehend him. Firstly, he had changed his name to Donald Brown and, of greatest concern, he had become a gun-totting bank robber.

From Zurich With Love

Hume had made £2,000 from selling his confession to the murder of Stanley Setty to the Sunday Pictorial, but he soon needed more funds. It was later reported that with the money from the article, Hume flew out to Switzerland, and began to set up a new life for himself there.

However, on 2 August, 1958, Hume went to the Midland Bank in Brentford, arriving two minutes past the weekend closing time of 12:30pm, and proceeded to knock on the door of the branch. A 24-year-old bank clerk called Margaret Kirby had recognised him from earlier in the day. He had asked about opening an account, so she opened the door to speak to Hume. She was one of four staff in the bank who quickly came face to face with a revolver wielding bank robber, a man who was definitely capable of murder. Within seconds, Hume had shot Frank Lewis, a 31-year-old bank clerk who had moved towards him. “Get back, the rest of you or I’ll shoot again,” Hume told the frightened employees as he directed them into the bank managers office. He commanded them to open the safes and eventually managed to get away with what the Columbus Ledger states was around $3,360. Hume wasn’t only intending to make a comfortable escape from the scene after the robbery, he was also intent on fleeing the country.

In Zurich, Hume had struck up a relationship with a peculiar Swiss lady named Trudi Hofner. Hume, who was known to Trudi by the name “Johnny Bird,” had wined and dined Hofner, with it being reported that he took her out for champagne and oysters. The relationship was flourishing, with Hume proposing to a “deliriously happy” Trudi and she accepted. When Hume first started visiting Zurich under the name Johnny Bird, he had stayed at the St. Gotthard Hotel. Detectives later showed pictures of Hume to Mr. Fritz Widmer, the hotel manager, who identified him as “The American.” The first time Hume had stayed at the hotel. He occupied Room 325 and signed the registration form as John Bird. Mr. Widmer claimed:

“While he was staying here there were complaints from guests that their luggage had been broken open in their rooms, and jewellery and money had been stolen. A woman in the room next but one to that occupied by this man lost jewellery. Because his room was so close we searched it but found nothing. He did not have a lot of luggage. About a month later he came back to the hotel and this time stayed in room 307, again on the third floor. When he left that time I gave instructions that if he came back he was to be refused a room.”

On 3 June, while the Sunday Pictorial confession pieces went to print, Hume had returned to Britain. After he had robbed the Midland Bank, Hume had flown back to Trudi in Zurich wearing the uniform of a Canadian Air Force officer. He left her again on the 11 August, claiming that he had to go to Canada, only returning to Trudi on 23 August. He then hired a car to take him and his future wife to meet her entire family in Lutzwil, near Berne. By early November, the diamond ring which adorned Trudi’s finger, along with the various other expenses, had seen Hume’s funds run low again. It was around this time that a public announcement was made in a Zurich newspaper stating that Trudi Hofner was set to marry Mr. John Stephen Bird.

On 12 November 1958, Brian Donald Hume, now known as Donald Brown, had flown back to Britain and walked into the same Midland Bank branch in Brentford which he had previously robbed. This time Hume was carrying two guns and when Margaret Kirby saw him, the event was later retold like this:

““And there he was – the Irish-man!” she [Kirby] was to say later. “He had two guns and he was saying ‘I’m taking over now!’ She shouted to warn her fellow employees: “The Irishman’s back! Get downstairs! Lock yourself in!”

The bank had increased the number of staff from four to twelve after the previous robbery and they seemed well prepared for another such experience. On the second raid, Hume got away with no more than $600 and the Midland Bank went on to offer a $14,000 reward for the capture of the robber. Scotland Yard had been making inquiries related to the robbery with their counterparts in Dublin and Paris, while also requesting from the French that Interpol become involved in the man hunt, with investigators believing that culprit was heading towards the continent. Now that Scotland Yard and Interpol were both on the hunt for this dangerous bank robber, it was only a matter of time before they identified Hume. Police traced the bank robbers movements during the day of the heist and discovered that he had boarded a Southern Railway train at Kew Bridge, where he had left his raincoat at the station. It was at this point in the investigation when Scotland Yard and Interpol both put out APB’s on the whereabouts of Brian Donald Hume. However, now they referred to him as “Donald Brown” and erroneously stated that his previous name was Donald Brian Hume, mixing up his forenames.

Whether this in any way hampered the efforts to confirm Hume’s whereabouts, it was going to be on the European continental mainland where he next emerged. Some reports during this period also named Hume as “John Lea Lee,” “Terence Hume,” as well as the aforementioned “John Stephen Bird.”

In the last week of January 1958, everything came to a head. Hume told the doting Trudi:

“I cannot marry you, I am a bad boy. I came back with a gun. I spy for the Soviets. I need a pistol because I fear for my life.”

A few days later, Hume tried to rob a Gewerbe’s bank in Zurich. Hume had walked down the Ramistrasse carrying a box in one hand to conceal the gun which he was holding in the other. None of the staff had noticed Hume until he had already crossed the lobby and vaulted over the counter. A bank clerk named Walter Schenkel rushed towards Hume who, like he had done during his first bank robbery in Britain, shot the bank employee in the stomach. The robbery was not going as Hume had planned and the employees were clearly not intending to shuffle into a back room to hide from the assailant. Another employee named Edwin Hug threw a waste basket at Hume’s legs, who then ran at Hug, beating him in the head with his pistol before Hug fell back stunned. Hume was soon rattling and pounding the cash drawers in an attempt to open them, but to no avail. Hume vaulted over the cashier desk to make his escape, but he was soon being pursued by shouts of “stop thief!”

Out on the streets of Zurich, various passersby also began to chase the panicked Hume along the Limmat River embankment, an area which is made up of narrow lanes. As Hume burst out of the alleyways and onto a local square, a taxi driver named Arthur Maag was alerted to the commotion and stretched out his arms to stop Hume. Maag fell dead almost as soon as Hume had shot him.

The pursuing party almost completely halted in their tracks, except for 25-year-old Gustav Angstmann, a pastry cook, who began a dangerous cat-and-mouse chase through the alleyways of Zurich. On every occasion when Angstmann got too close for Hume’s comfort, he swung his gun out towards his pursuant who ducked in and out of doorways to avoid being shot. However, the narrow alleyways eventually opened up onto a main thoroughfare called the Limmatquai and Hume hesitated for a moment. Angstmann was relentless, he rushed towards Hume and grabbed the gun, using his excess strength to overpower him. Screams of “Lynch him! Lynch him!” sang out on the streets as the police arrived quickly to take Hume into custody.

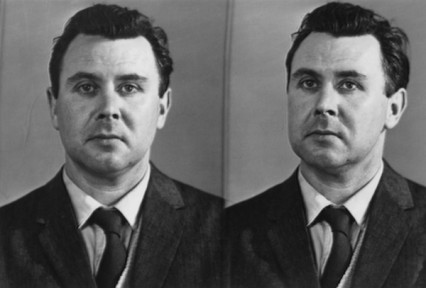

On the 30 January 1959, police in Zurich arrested a dark haired man with a plump face who had attempted to raid the bank that morning. The bank robber, who managed to get away with 215 Swiss francs—which was equivalent to about £18—was soon to be identified as none-other than the infamous Brian Donald Hume himself. When the Swiss police apprehended Hume, he gave his name as “John Stanislav” and refused to give any further information until, as always in the case of Brian Donald Hume, he could begin to make up a more elaborate story. The police were still trying to discover his nationality and initially questioned Hume in German, French, Polish, English and Russian, with Hume claiming that he was in fact of Polish stock, and stating that his parents were naturalised American Poles. He told investigators that he was an employee of an American airfield in Germany and the Swiss police may have normally been hooked into believing this very skilled con artist, who was capable of getting away with murder. However, by this time Interpol had already become involved. Within an hour they had Hume’s real identity and the game was almost at its conclusion.

The capture of Hume saw an instant reward of 1,000 Swiss franc – about £83 – awarded to Gustav Angstmann for his bravery – it is noted in one article that “Angstmann” ironically means “the frightened man.” Swiss detectives listened to Hume’s story and reportedly “said politely that they didn’t believe it.” They contacted London, which sent ‘a double wired picture of Hume via a telephoto machine, and twelve minutes later they had received Hume’s fingerprints. The Swiss Police then officially announced that they were holding Hume in custody. They also quickly made a £4,000 payment to the family of the slain taxi driver from a special police insurance fund.

Hume was going nowhere. The Swiss authorities made it clear that they were dealing with a self-confessed murder and they intended to put him on trial for murder in Zurich. The previously mentioned reporter Robert Traini comes up again during coverage of Hume’s Swiss trial in an article subtitled: “Was it the name of Hume’s THIRD victim?” Hume was now a confessed double murderer, killing both Stanley Setty and the unfortunate Swiss taxi driver Arthur Maag, but Traini suggests that there may be a third murder mystery to unravel. The passport which Hume had been using in Switzerland was linked to a real person named Stephen Bird who had been born in Liverpool. Hume had used Bird’s birth certificate to gain the false passport – he also changed his hairstyle, grew a moustache, and donned glasses for the picture he used for the document. Traini reported that passport officials in London were quite satisfied that the birth certificate was real and the particulars given were genuinely of one Stephen Bird.

On 21 February 1959, it was announced by Dr. Dieter von Rechenberg, who had been appointed as Hume’s counsel for the coming trial in Switzerland, that his defence was to be based on “extenuating circumstances due to partial insanity.” He had already confessed to the crimes but there were still going to be more twists and turns in the case of Brian Donald Hume, including at the end of February 1959, when it was announced that one of the key witnesses in the case against Hume had become very ill. Mr. Walter Schenkel, the bank cashier who Hume had shot, was rushed to hospital with a blood clot in a main artery.

By mid-April, the man heading Hume’s defence, Dr. Diether von Rechenberg announced: “Hume appears to be completely crazy.” He also warned that, although the indictment was being prepared, it may take several months before the case made it to trial. Swiss investigators were in no way giving up on the prosecution, in fact they were investigating the possibility that Hume had robbed more banks, possibly in Montreal, during 1958.

By August 1959, Hume was not in a good mental state. He was put in solitary confinement in Zurich after he attempted to rush the guard who was bringing him food. The stress of the coming trial was clearly taking a massive toll on Hume’s very complex and fragile mental state and, in the end, the Swiss brought 5 charges against “Donald Brown,” listing them as; murder; attempted murder; robbery; issuing repeated threats; and contravention of the Aliens Act. The indictment in relation to the latter charge stated that Hume had travelled to multiple countries in 1958, including, Switzerland, Britain, France, West Germany, the United States and Canada. It also listed him as using various names, including, Stephen Bird, Micheal O’Brien, and Anton Stanislav. The defendant was due to be tried in front of three judges and a jury at Winterthur.

Less than three weeks after the charges had been brought, the Sunday Pictorial were again busy reporting on the inner workings of Brian Donald Hume’s complicated life. This time, journalist Victor Sims writes:

“A lovely, honey-blonde Swiss girl flies home to Switzerland this week to see the man she planned to marry stand trial for murder. The girl is Trudi Sommer, 29, who has been working in a hairdressing salon at Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffs. The man she hoped to wed is Brian Donald Hume, 39, self-confessed killer wanted by British police for questioning about armed hold-ups at a Brentford (Middlesex) bank.”

In reality, Hume had made no attempt to communicate with Trudi Sommer from the time he was arrested. At the trial, Trudi would get to see her mysterious estranged lover shackled in chains, even though, by Swiss law, she was not compelled to attend the trial. The trial was due to open on 24 September 1959, and it was never going to be long before Hume started telling elaborate new tales which could only be semi-verified. A couple of days into the hearings, Hume was testifying that he had been working as a Communist spy for East Germany. He claimed to have photographed an American military airport in Maine and told the court that he delivered the photos to the East German government. Hume also claimed to have run errands for the atomic spy Klaus Fuch’s, and also hinted that he had been involved in tech-espionage in Montreal.

The Sunday Pictorial had found another way to stay close to the story by having their reporter Victor Sims on-hand to drive Trudi Sommer to see Hume. This way Sims was able to successfully document the eventual reunion between Trudi and her jailed fiance:

“It began with Hume, wild-eyed, hurling insults at Trudi, twenty-eight-year-old honey-blonde hairdresser. It ended an hour later with tears, hugs and kisses.”

Bravado and drama aside, the case against Brian Donald Hume that was put forward by Swiss prosecutors was a strong one. On the 30 September 1959, the Birmingham Mail printed a small piece entitled: “Hume is Guilty.” Hume had been found guilty on all counts with the jury deliberating for 2 hours and 56 minutes to reach their verdict. Brian Donald Hume was taken from the court immediately. As the realisation dawned on Hume that he had been found guilty, he reportedly began laughing like a child and dragged his guards around as he ran down the main court, building jumping three steps at a time, until he was eventually bundled into a van and taken to prison. Justice had been served and Hume was given a life sentence of hard labour.

Even though the press were mostly staying clear from reporting on anymore of Hume’s extravagant claims, in 1965 he was still able to get a headline in the paper, regardless of his situation. In the Western Daily Press, Hume claimed that Timothy Evans had confessed to murdering his baby daughter. Hume’s supposed evidence was read out at what was being called the ‘Evans inquiry’ but Hume’s new elaborate claim was not going to redeem him on this occasion.

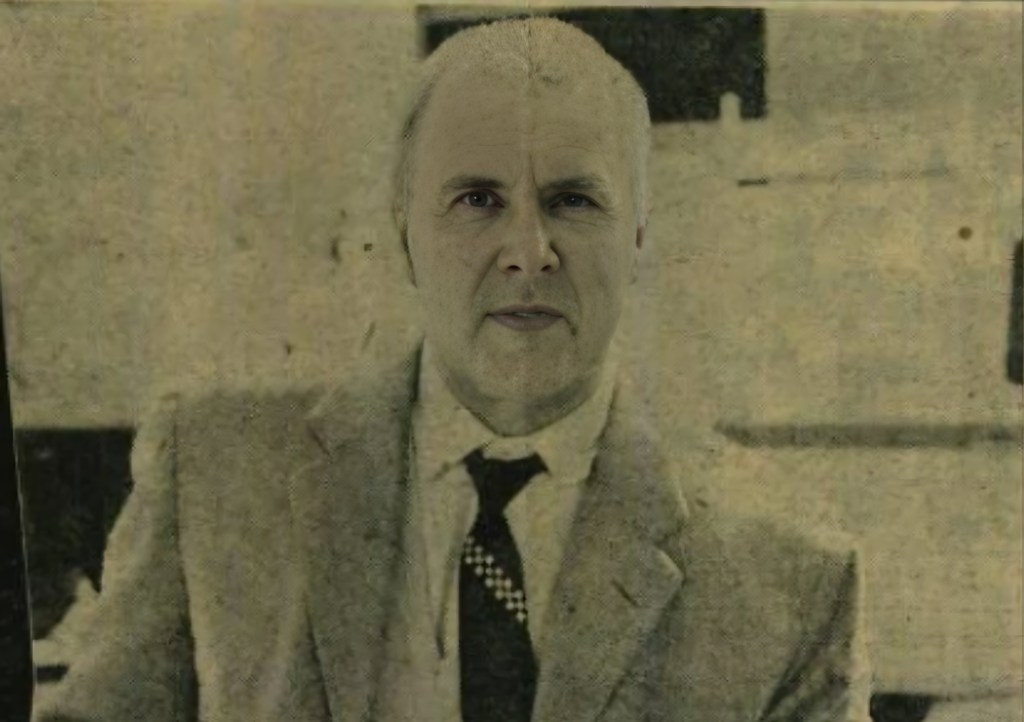

By the mid-1970’s, Hume’s mental state had deteriorated further. He was held in solitary confinement after attacking the governer of the prison where he was being held, as well as various guards, all of whom were fed up of dealing with the mad Brit. Eventually, after years of legal wrangling, Swiss and UK authorities came up with a deal which saw Brian Donald Hume return to Britain.

On Friday 20 August 1976, Hume returned to Britain in chains. He wasn’t to see a new trial on his return to the UK, there was no fanfare and little note that he was back, the UK authorities instead transferred Brian Donald Hume straight to Broadmoor Mental Hospital, a place where he was able to live among like-minded folk. However, the staff and patients at the infamous British mental hospital weren’t planning to show any affection towards Hume. The Sunday Mirror newspaper reported on 22 August 1976 that:

“Double killer Donald Hume’s admission to Broadmoor will tarnish the top security hospital’s reputation, a former patient said yesterday. Mr. Peter Thompson author of the book Back from Broadmoor, said: “It is a hospital, not a prison. There are nearly 100 people there who have not committed a crime.”

Mr. Thompson claimed that Hume’s new home was to see its public image set back “fifteen years.” Hume had changed his name again while he was in prison to Brian Brown but there were no more outs for Brian Donald Hume. Hume spent most of the rest of his time incarcerated in Broadmoor, except in 1988 when he was transferred to St Bernard’s psychiatric hospital. His transfer led to a DHSS spokesman stating:

“When someone is admitted to a special hospital like Broadmoor we don’t lock them up and throw away the key. They undergo a process of treatment and rehabilitation according to their individual requirements. A transfer of this kind would indicate that the level of security needed is not as great as it was previously – that the patient is getting better.”

In fact, by this time, Hume had spent four years being allowed out on escorted trips and his transfer to St. Bernard’s was a step in “the easing of his security,” as the latter article puts it. Hume was heading towards freedom again, although, in 1992, he was still being mentioned as an inmate of Broadmoor. Around this time, other erroneous reports also claimed that his incarceration in the psychiatric hospital had been following the murder of Stanley Setty. It seems that sometime during the mid-90’s, Brian Donald Hume’s bizarre life became a foggy memory in the collective consciousness. Soon after this last mention of Brian Donald Hume in 1992, he was released quietly back into the public. In July 1998, the Paisley Daily Express reported on the pathetic end to the life of Brian Donald Hume. The piece, entitled ‘Double Identity’ read:

“A notorious double killer had to be identified from his police fingerprints after his body was discovered miles from his home. Donald Hume, 78, who died of natural causes, lay unidentified in a mortuary for a week after he was found dead in the grounds of a hotel in Basingstoke, Hants.”

Brian Donald Hume passed away of natural causes, alone, but a free man. At the time, the authorities doubted that they would have been able to identify his corpse without the fingerprints from his original conviction. Almost 50 years after he had murdered Stanley Setty using an SS dagger, Hume also left the mortal coil.

There was no funeral recorded, no friends or family to mourn his passing, Hume died in ignominy.

Telling the entire story of Brian Donald Hume, the man who murdered Stanley Setty and Arthur Maag, has been a big task for this author. To investigate such a case in detail often means the writer must become emotionally attached to the characters and events involved. This case was no different.

Although Hume’s life was astonishing in places, he was still a murderer and the real story of his life was scattered amongst hundreds of articles and documents which individually failed to give a complete account of all the main events. Johnny Vedmore strives to bring you all the information available on the subjects which he reports on rather than what is convenient for publication. This sort of work is very intensive and the articles you’ve just read have been researched and written over a period of more than a year. To support this style of journalism please support NEWSPASTE in whatever way you can.