In 1949, a stocky Iraqi car dealer based in London was murdered, chopped into pieces and the dismembered body parts were thrown from a light aircraft above South East England. The events which followed became a captivating murder mystery which enthralled a post-war public and led to the bizarre trial of Brian Donald Hume, the man who would get away with the brutal murder of Stanley Setty.

Sulman “Stanley” Setty had been born in Baghdad to his mother, Katoune Setty (born Shashoua) in around 1904. Stan was one of four siblings, he had a sister named Eva, and two brothers called David and Max Setty. They were from a major Sephardic Jewish family of the Ottoman Empire – Sephardic Jews being a Jewish diaspora population which became prominent in established communities throughout the Iberian Peninsula. Sephardic Jews were mostly expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in the late 15th century, but they continued to carry their distinctive Jewish identity with them to North Africa and the Middle-East, usually along the farthest reaches of the ancient Silk Road trade routes. The line of the Setty family we’re examining had settled in Iraq for sometime, but another branch of Stanley’s family had also been born in Lebanon in the late 1800s.

By the mid-nineteen-twenties, Stanley Setty was a 24-year-old “shipper” operating his business out of 44 Princess Street in Manchester, England, while also registered as maintaining a residence at 17, Circular Road, Withington. Stanley was involved in significant business dealings from a surprisingly early age. Stanley and one of his older brothers had been recorded as running a business when Stanley was only 16-years-old. When the business failed, Stanley’s brother hid out in America, leaving the sixteen-year-old Stanley to face the music alone. The firm failed with nearly £15,000 in liabilities and about £5 in assets on the books. Because Stanley was only sixteen at the time and still classed as a minor, he was not adjudicated as a bankrupt. Eight-years after a young Stanley Setty had narrowly avoided becoming bankrupt, his poor business dealings had led him to being hauled in front of Manchester Bankruptcy Court, recorded in the 28 April 1928 edition of the Guardian newspaper.

Setty had started his own business in 1926 after saving £300, calling himself a shipping merchant, but in reality everything he was buying was sold to the real shipping merchants. By 1927, Setty had begun buying mainly on credit and, in just a year, he had eventually racked up liabilities of £7,257 with zero assets to declare. During the court hearing, Setty claimed that he had lost £2,000 of his overall debt through gambling and said he kept no books of his business dealings at all. Setty did produce an invoice book in court but large chunks of his only accounts, which were meant to house the perforated duplicates of the receipts, had been torn out. There was other suspicious behaviour brought up in court that suggested Stanley Setty was hiding what he was really doing. The Guardian article from the time states:

“A considerable list of transactions was submitted to him by Mr. Chapman, showed that he [Setty] had bought goods at certain prices and on the very day of purchase had sold the goods again at lower prices and a discount, thus sustaining considerable losses.”

In fact, the trustees involved with the case were able to trace most of the sales Setty had made. They recorded that out of ninety sales, seventy-eight were under cost price, with the losses averaging at between 10 and 15 percent. In the hearing, Setty denied being a ‘shipper’, claiming that the description was misleading, because, in fact, he claimed to be doing no “shipping” at all, even though that was what his business enterprise was originally set up to do. Setty came clean to the court that he had merely sold to shippers and, he told the court, he believed that distinction should be made clear. Although Setty had tried to wriggle his way free of potential charges, his ruse failed, and less than a fortnight later he was remanded in custody and the prosecution alleged that he had committed a “series of offences of obtaining goods on credit by fraud.” Setty was arrested by Detective Inspector Haughton and was quoted in another Guardian column as saying: “I don’t wish to reply until I have seen my solicitor.” The charges related to the obtaining of cloth goods on credit by fraud to the amount of £160 from Burgess, Ledward, and Co., and, although Setty had returned from visiting his father in Italy to take part in the trial, Inspector Haughton asked for substantial bail to be set, with the bail eventually being in the region of £200.

Following further police investigations over the following few months, Stanley Setty eventually pleaded guilty to 23 offences under the Bankruptcy Act and the Debtors Act. On sentencing at Manchester City Sessions on 1 August 1928, Setty’s mother was carried out of the court by four police officers while struggling and screaming out: “Oh my innocent little boy. Take me with him.” Stanley’s mother, Katoune Setty, made the pages of various newspapers with her dramatic courtroom antics with headlines such as “Mother’s Cry in Court” and “Innocent Little Boy” becoming the centre-piece of the cases coverage.

By 1938, a year before World War II and 10 years after his jailing for fraud, Setty had been forced into trading in the shadows. His bankruptcy was crippling his ability to trade and he made a request to Manchester County Court for his discharge from bankruptcy. However, on reviewing the details of the case, Judge T. B. Leigh refused the bankruptcy discharge, with his comments being reported as:

“That a man should continue to be under the stigma of being an undischarged bankrupt and that it should be made difficult for him to go on trading except in a small and hand-to-mouth fashion was something which, although it might be a painful experience for the bankrupt, nevertheless was a wise precaution in the interests of the trading community.”

Stanley Setty wasn’t recorded as disputing his bankruptcy again after 1938. During the 1940’s, Stanley’s brother, Max Setty, was running Crown Garage in Albany street, London, a road where Stanley had also based himself in separate garage next-door, becoming known as a car dealer amongst other things. In the court case surrounding Setty’s murder and mutilation, Cyril John Lee, an ex-artillery officer, told the court that he got to know the Setty’s garages quite well while he was living in nearby Cambridge Mews between November 1946 and March 1949. Mr. Lee gave evidence stating that the garage had been used mainly by locals who needed their cars fixed at first, but later he noticed other activity, stating:

“Halfway through my stay there, a rather different sort of people started appearing, Not the sort of people I would like to see round my doorstep.”

However, Mr Lee’s statements would later come in to serious conflict with the truth. Whether or not the Setty garages were dens of villainy or not, Stanley Setty had become know as man who carried around at least £1000 in cash wherever he went.

In fact, Stanley Setty had made a lot of money during World War II when he reportedly became the mastermind behind the “Petrol Coupon” racket. During the war, Petrol was heavily-rationed and the coupons issued for its purchase were, as a Black Country Bugle article from 23 September 1999 puts it “worth considerably more than their weight in gold.” The previously mentioned article also talks about Stanley Setty’s role in the proliferation of these coupons, stating:

“Setty turned to Birmingham craftsmen for ‘petrol-coupon plates’ which were soon ‘flooding the black market’. Like the banknotes of the previous century they were ‘works of art’ and soon put Setty in the millionaire bracket. He developed legitimate businesses in several fields of commerce, including car-sales ‘fuelled’ by Black Market petrol for even when the war ended, petrol remained ‘on the ration’ and Setty’s fake plates continued to bring him rich dividends.”

Even though there may be elements of truth to the claim that Setty dealt in the petrol-coupons of war-time and post-war Britain, he was never arrested or convicted for doing so. However, other reports also insinuate that Stanley Setty was more than just a simple car dealer.

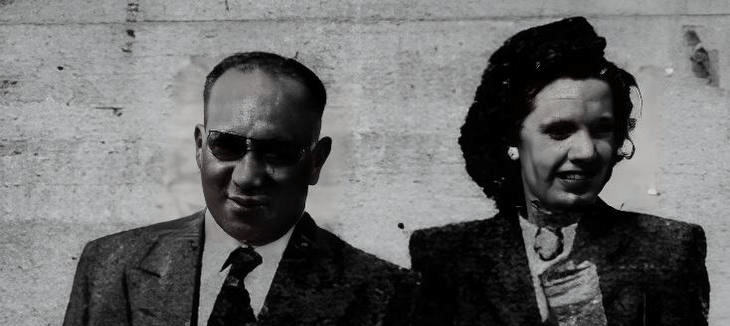

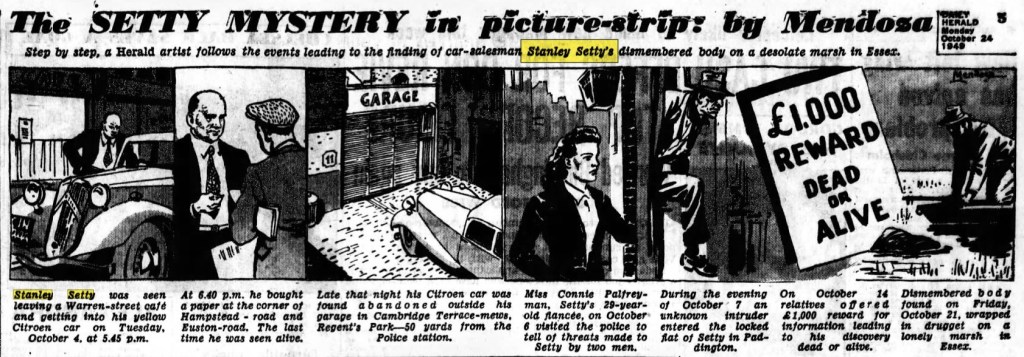

The Disappearance of Stanley Setty

It was Tuesday, 4 October 1949, Stanley Setty, a well known car dealer on the Warren Street motor market, prepared to complete a car deal where around £1,500 was to be exchanged. By 5:45pm the same day, he was seen sitting in his own car while his assistant had gone to the bank to cash a £1000 check for him that was from the sale of a Wolseley automobile. At 6:40pm that evening, Setty bought a newspaper at the corner of Hampstead Road and Euston Road and later that evening, Stanley Setty’s car was seen sitting outside his garage in Chester Place, and was still parked there in the morning. However, Setty himself had vanished.

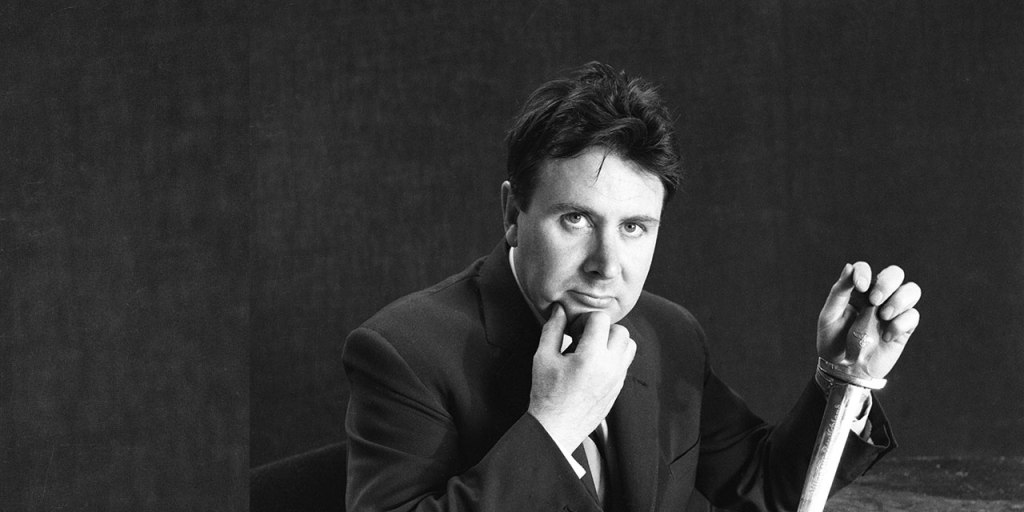

Stanley’s brother, David reported Stanley missing, concerned that his brother would never leave his beloved car, a yellow Citroen (some reports claim his car was cream coloured), outside his garage all night. Indeed, David Setty’s concerns had not been for nothing, Stanley Setty was dead. Within two days of Stanley being reported as missing by his family, it was said that both Scotland Yard and the Setty family believed he had been murdered for the £1,500 (some reports claim it was £1000) in £5 notes which he had been carrying with him at the time he went missing.

Stanley had been living with his sister and brother in law at Maitland Court in Bayswater Road, and they had been expecting him to return from the car deal later that evening, with his sister, Mrs. Ouri, stating:

“Stanley was always home by 11pm. He did not drink and had very few women friends. We noticed that his Citroen was parked in the mews outside his garage at about 10.30 on Tuesday night. We thought he would soon be in. But he did not turn up.”

Although Setty’s sister had painted a lonely picture of Setty, he had a fiance, 29-year-old Connie Palfreyman. They had known each other for around three years, and she was quoted as saying at the time: “I used to see Stanley every day. We hoped to marry soon.”

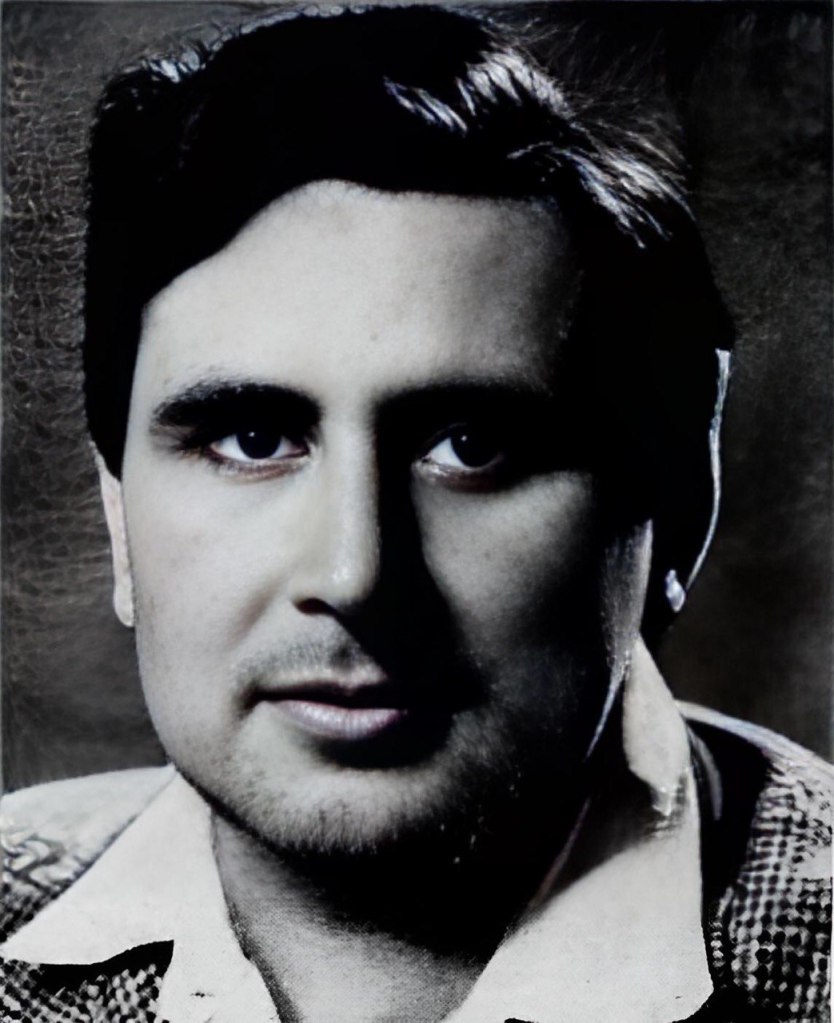

Detectives tried to trace the supposed seller of the Jaguar in Watford which Setty was meant to have been going to buy, but soon decided that the offer of a cheap car was most likely used as bait to entice Setty into a trap. In the Daily Herald paper from 6 October 1949, Setty was described as:

“5ft. 3in. tall, sallow complexion, dark hair, round face, large nose, and well built. He was wearing a blue suit and brown shoes when he went missing.”

The following day the Courier and Advertiser published a small article on page 3 of their publication entitled: “Man with £1000 in his Pocket Disappears,’ it was being assumed by most people that the large amount of cash which Setty was carrying had probably resulted in his eventual murder. On the following weekend to his disappearance, Ascot bookmakers were told to: “Watch for Stanley Setty’s fivers.” Police had already released the serial numbers from the 200 notes, reported as M41 039801 to 040000.

Chief Inspector S. A. Glander, a member of the CID, was reported as engaging in ‘secret inquiries’ in connection to what was believed to be the ‘biggest car racket’ in Britain in relation to Setty’s murder. Glander had posited that Setty may have been a target of a gang who specialized in stealing almost new cars. However, further inquiries concerning the gang in question seemed to lead no where. The detectives of Scotland Yard took this opportunity to head to Paris to make some inquiries, with the Daily Telegraph stating that it was a city where “Setty is known to have friends.” The Surete Nationale in Paris were asked to check if Setty had any assets based in Paris, but no such line of inquiry paid off. On 10 October 1949, someone called 999 reporting that a man resembling Stanley Setty was seen driving a car towards the Great West Road from London to Bristol.

On the 15 October, it was reported that a firm of solicitors, Ronald M. Simons, of Rego House, the legal firm which were representing Setty’s family, offered a £1,000 reward for information leading to the finding of Stanley Setty. The Sunday Pictorial reported the following day on a tip to police that “a white-faced man, the image of Setty” had been seen being driven in a black saloon near Boreham Wood. On 19 October, it was confirmed by Maltese police that a man who was thought to resemble Stanley Setty, and who had arrived on the island recently, was not the London car dealer. Although the hunt for Setty in Paris had been inconclusive, the ambiguity of the situation saw the press report on Rachel Setty, Stanley’s sister-in-law, arriving in Paris on 21 October. The Metropolitan Police had pulled out all the stops the find the missing Stanley “Man with the Fivers” Setty, but so far they were coming up empty handed. Scotland Yard instructions at the time were for police to “search every open space, every bombed building – particularly basements – and shelters, or any other likely place “for a body.””

The police hunt started to get close to the truth two days before the dismembered body of Stanley Setty was recovered from marshland. On the 21 October, a Scotland Yard conference announced that they had requested help from Special Branch for what was referred to as “priority aid” in the search for Stanley Setty, who at that point had been missing for 17-days. The Special Branch went straight to work and began to check all fields in the Home Counties where aircraft take off and land. The day after the Special Branch had become officially embroiled in the case of Stanley Setty, the headless, dismembered, partly decomposed body of the 44-year-old Iraqi washed up near Burnham-on-Crouch in Essex. It wasn’t until the day after the gruesome discovery, on 23 October 1949, that newspapers such as the Sunday Dispatch reported on a riverside find. The opening lines of the main article reads:

“The dismembered, headless body of Stanley Setty, 44-year-old car dealer who disappeared with £1,500 in notes in his pocket three weeks ago, was found on the foreshore of the River Blackwater at Tillingham, Essex, last night. His head and legs were missing. They had been roughly cut off, apparently with an axe. There were seven stab wounds in the chest.”

Setty’s hands were taken to Scotland Yard, where Chief Superintendent Fred Cherrill, who was head of the fingerprint department, compared skin from the finger-tips with prints lifted from Stanley Setty’s household furniture. To take Stanley Setty’s fingerprints, Cherrill’s assistant Detective Bill Turpie was forced to become a veritable Buffalo Bill. They removed the skin from the ends of Stanley Setty’s fingers and Turpie then wore the dead man’s finger-skin over the tips of his own fingers. This gruesome technique yielded results, with Scotland Yard able to officially confirm the identity of the headless, legless, mutilated corpse, as that of Stanley Setty.

The initial inquiries into the disappearance, and now death, of Stanley Setty led to some mixed reporting in the proceeding days after the discovery of his corpse. The Daily Herald ran a front page piece about the Setty murder on 24 October, entitled, ‘Setty Killed in Hide-Out. Police seek gang H.Q.,’ where reporter Robert Traini claimed it was believed Setty was taken to the hide-out of a gang and beaten up. In the article, the author states:

“Detectives believe that he got into a car in which at least two men were waiting. They believe he went willingly – the men had probably fixed an appointment – and was driven to a building somewhere near. There he was suddenly attacked. His hands were bound behind his back and his kidnappers tried to get from him something they wanted urgently.”

The wild speculation which Robert Traini claimed as journalism, was partly infused with elements of truth given by the detectives in charge of the case. The investigators involved with the Setty murder had already been building up a theory in this enthralling case, a theory which then appeared to manifest before them. The disappearance of Stanley Setty hadn’t only captured the imagination of the detectives involved in the case, along with the journalist involved in its coverage, it had also captured the public imagination, and a desperate collective cry for answers began.

To be fair, the horrific reports of the dismembered remains of Stanley Setty had rightly caused a lot of public speculation. The body of Stanley Setty had been found within the Dengie Marshes in Essex by Sydney Tiffin, a 47-year-old farm labourer who stumbled across the gory remains while shooting wild fowl. At first Tiffin thought he had found just a bundle of old bedding, including a grey blanket which had been stitched. On breaking the stitches, the body of Stanley Setty was revealed. Dr. F. C. Camps, the pathologist assigned to examine Setty’s body – later referred to as “the scientist who trapped killers” – found several stab wounds on the torso. By the 25 October, the Herald Express reported that £5 notes known to have belonged to Setty had been traced to Southend. This discovery was being touted as very important and the article expressed the expectation that developments were just around the corner. Indeed, Scotland Yard believed they were on the brink of a breakthrough in the investigation. The day after the supposed developments had been promised by the Herald Express, more than 200 detectives were actively involved in the Setty investigation.

Indeed, the push towards a conclusion in the mysterious murder of Stanley Setty was in its final throes. On the 27 October, it was announced in a Herald headline that: “Setty Thrown from Plane: Three Men Sought,” with the paper reporting that Scotland Yard had received that information the day before with further reports stating that all London airports had been asked to look out for a three-seater Proctor aircraft with a cracked window. By this time, the movement of all small aircraft in the area between the 4th and 12th of October were now being examined closely. By the evening editions of the 27 October’s newspapers, it was being reported that vital developments were expected that very evening.

The following day, the Metropolitan Police announced that they had detained a man at Albany Street police station in connection with the murder of Stanley Setty. On the 29 October 1949, Brian Donald Hume was brought to Bow Street Magistrates’ Court for a hearing which lasted three minutes. When Hume was charged with Setty’s murder, he told the arresting police officer:

“I did not kill him.”

The Flying Smuggler

Earlier that month, a man named Brian Donald Hume drove Stanley Setty’s mutilated and beheaded body, wrapped up in felt and blankets, towards Elstree Aerodrome. He had been trying to not draw any attention to himself as he drove the car cautiously with his dog Tony besides him. Tony was a half-husky, half-Alsatian, which Hume had bought for £1. “This was no ordinary dog,” Hume would tell the Sunday Mirror newspaper in June 1958, “We had a mutual understanding. And Tony was the only one who shared my secret about the murder of Setty.” In a later article, Hume described the moment Setty had kicked Tony:

“One afternoon, in August, 1949, I turned up at his garage. My dog Tony was with me, as usual. I quite liked Setty until that afternoon. But he kicked Tony, who had climbed into a car and scratched the paint. Tony yelped with pain. It was the worst thing Setty could possible have done. For Tony meant more to me than did my wife or my baby daughter. Nobody could do that to my pet dog and expect to get away with it. I kept my ears open and heard a few things about Setty. There were whispers that he had done “time” for fraud some years before. I heard stories that he had claimed that he was having secret meetings with my wife. I heard stories that “Stan” had taken my wife out drinking a couple of times in the afternoon. I was fast getting the needle with Setty.”

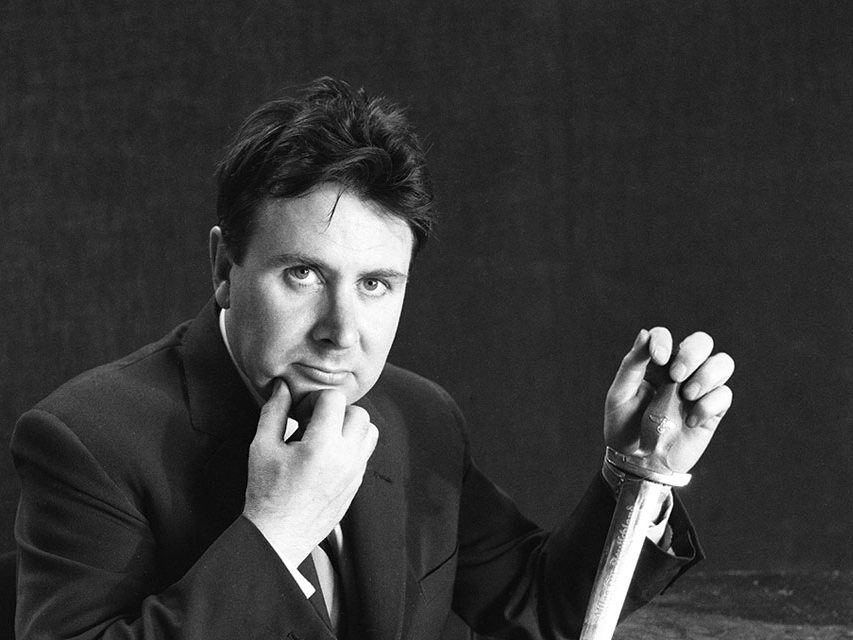

Hume was spotted arriving at Elstree Aerodrome by William Davey, an aircraft fitter, who also witnessed Hume loading two packages into his Auster aircraft. Brian Donald Hume had first caught a glimpse of Stanley Setty as he was standing outside a cafe in Warren Street. He described Setty in a Sunday Mirror article, stating:

“This man was big-boned, fourteen-stone, with dark eyes, swarthy, foreign-looking, and aged about forty-two. I was told that his name was Setty, and that he had changed it from Sulman Seti when he came from Baghdad years ago. We haggled over a car. He had a voice like broken bottles, and pockets stuffed with cash.”

Hume took to the skies above South-East England in his small plane with Stanley Setty’s dismembered corpse contained in two packages and he plotted a course towards the coast. At this moment, Hume was reminded of his first murderous childhood experience. His mother had kept forty hens and three cockerels when he was younger and one cockerel in particular became a nuisance to the young boy. The cock in question would charge Hume whenever he went into feed the birds. One day, Hume took his mothers small-bore gun and shot the bird, throwing the cock’s corpse into a cesspit, telling his mother that the bird had drowned by accident. The sight of the dead cockerel laying in the bubbling feces sat in Hume’s mind as he flew over South-East England with Setty’s dead body in tow. Brian Donald Hume, who will soon be referred to publicly as the “flying smuggler”, as well as also being called by other, more serious nicknames, later told investigators that he had been told to drop these packages into the sea from 2000 feet up. He also claimed that he had believed the packages contained forged petrol coupons and the printing plates used to make them.

On the night in question, Hume flew in a trajectory which took him alongside the Thames and on towards Southend. One of the parcels was reported to be “something heavy in a baked bean box” alongside a smaller package. Hume told investigators later that the adventure saw the “company director” make a cool £100, a fair rate of pay in the late nineteen-forties. Once Hume had flown past Southend Pier, he flung the packages out of the plane and proceeded to land at Southend Municipal Airport, where James Small, a member of the local flying club, later testified to seeing Hume taxi his aircraft to the hangar without any packages on board. Hume apparently explained to Small that he had had to abandon his flight and decided to return because of the poor weather. Hume was a member of the United Services Flying Club at Elstree and had hired a car especially to drive to and from the airport.

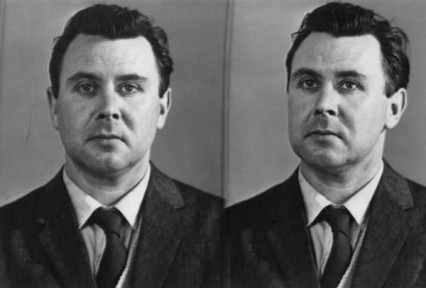

Hume was concocting a plan, an ingenious story, he was trying to get away with murder. By the 28 October, Hume was being held in police custody under the supervision of Detective Superintendent Colin Macdougall at Albany Street Police Station. He had been spotted staying at a boarding house run by Miss Cora Redmayne and her mother, who informed the police and cut any manhunt short. Even though his story began to unravel quickly, Hume kept to it, reportedly saying to Macdougall: “I can’t help you, I cannot see where it has anything to do with me. Setty has not been to my place.” Superintendent Macdougall responded to Hume: “I understand you hired an aeroplane at Elstree aerodrome on October 5, on which you loaded two parcels and took off for Southend at 5pm.” Hume tried to deny the reports of cargo stating: “It’s a lie. I put no parcels in the plane. All I had with me was my overcoat.” However, witnesses had already given statements to the police contradicting Hume’s initial story.

Hume was clearly in trouble and he soon began making up an elaborate tall-tale which eventually saw him get away with the murder of Stanley Setty. Macdougall’s interrogation of Hume continued with the Superintendent later putting on the record:

“I again saw Hume at 2:30pm on October 28. I said: ’Have you been able to remember anything further about the three men you described. I have had many inquiries made, but they cannot be identified.’ He [Hume] said: ‘No I have been thinking hard, but I cannot tell you anything more about them. You should be able to pick them up in Warren Street.’”

Hume eventually told the investigators in charge of the case that he had been given this task by three men who he described in detail. The first man Hume referred to as Max or Mac, and was said to be around 35 years old with fair hair, a poor English accent, and reportedly had a habit of polishing his ring on his coat. The second man was referred to by Hume as “The Boy”, with brown hair and a receding hairline, Hume told police that he wore steel-rimmed glasses and bright brown buckled shoes. The third man was described as being called “Green”, “Greenie”, or “G”. He was said to be a Cypriot or a Greek man of about 31 or 32. His colourful name may have come from the flashy green suit which Hume described “Greenie” as wearing. Once Hume had returned from his assignment, he arrived at his home, where he claimed that he was met by the three conspirators.

They had a third, much heavier, package with them on this occasion and soon offered Hume more money to do the same again. Hume told investigators that he got into the car with the three men, but the package was so large that there was nowhere for him to sit, leaving him to sit on the lap of “The Boy” whilst they drove him back to his apartment which he shared with his wife. As a smuggler, Hume may have been accustomed to strange men bearing weird and weighty packages, yet Hume claimed that nothing had tickled his suspicion until after the three men left and one of the package began to leak with what Hume said appeared to be human blood. Hume’s imaginative story was to be quickly written-off in court as “a complete fantasy” by the prosecuting counsel, but this so-called “fantasy” was due to pay dividends. Hume had constructed an alternative scenario where he was still somewhat guilty but not culpable for murder.

A day before Halloween, 1949, men in black hats queued up at Bow Street as the sensational Setty case, which had been plastered all over the newspapers for weeks, began causing a commotion. It was later reported that competition for entry to the trial was so hotly contested that one woman bought her place in the queue for £2 while others in the queue offered their places for as much as £5. Brian Donald Hume had been remanded in custody for the murder of Stanley Setty and, wearing a blue-and-fawn check sports coat, grey flannel trousers, and an RAF shirt and tie, he stood in the dock of London’s Bow Street courthouse. The scene outside court was fascinating. A Sunday Pictorial article from the 30 October states:

“A long queue waited to enter the court. There were many men in long heavy overcoats and black Homburg hats, and crowds of young girls. Costermongers and Covent Garden porters streamed across the road to the court building. Traffic was held up. The Burnley football team, in town for their match with Charlton, were in court. Claret and blue rosettes of Burnley supporters sprinkled the queue.”

Many of the newspapers in the days following Hume’s arrest contained various pictures and references to the man accused of Setty’s murder. Hume’s wife, Mrs. B. D. Hume, was under constant guard by a team of CID officers. By the time of the second remand hearing which took place on 5 November 1949, about 50 people were outside the court waiting to catch a glimpse of Hume, who was hurried away after the trial, shielded in a long coat while he was spirited off.

Not everybody was a fan of Stanley Setty and his ilk. On 6 November, the Sunday Pictorial printed an article by Ralph Champion entitled, “Expose the Parasites!” which targeted the murdered Stanley Setty as a tax dodger and a parasite on British society. The article states:

“There is something wrong, indeed, when Stanley Setty can flourish as an uncrowned king of the used car business – ignored, apparently, by the authorities until one day he is murdered. This Sulman Setty from Bagdad had been gaoled for a financial offence. Twice he had been bankrupt.”

The thoughtless and inopportune comments were part of a series started the previous week by the Sunday Express who “declared war on the tax-dodging parasites, like Setty.” Brian Donald Hume however, was still the one being housed at the tax payers expense in Brixton Prison’s hospital block. Remanded alongside him was twenty-three-year-old David Raven, who was accused of killing his in-laws.

Before the actual trial of Hume for the murder of Stanley Setty had begun, there were three events in particular which were of note. Firstly, the Setty family put forward a ‘plea for a law of libel that would to protect the dead’, as termed by the Canberra Times on 8 November 1949. This plea was made by the legal team representing the relatives of Stanley Setty. The counsel for the relatives, led by a Mr. Durand, claimed that newspaper reports, some of them inaccurate, had hurt the relatives very deeply, stating in court:

“It is a thousand pities that a man, having lived perfectly honestly and respectably for so long, should form the subject of articles written purely for profit and of no benefit to the public.”

The second intriguing event to mark the start of this fascinating case was that the trial judge, Mr Justice Lewis became seriously ill on the morning of 19 January 1950 – he died a month later – leading to a new trial being arranged and a new judge being allocated to the case. The new trial would see Mr. Justice Sellers appointed as the presiding judge, with the prosecution team being named as Mr. Christmas Humphrey’s and Mr. Henry Elam, while Hume’s defence team was announced as Mr. R. F. Levy K.C. and Mr. Claude Henry Duveen.

The third intriguing event happened almost as soon as the trial had restarted, where a journalist named Duncan Webb was summoned to the court. Webb was pulled-up in front of the newly installed judge and warned that interfering with a witness was a common law misdemeanor. The journalist had sent a telegram to the Hume’s wife after apparently being told by her mother that “she had been spirited away.” The defence solicitor, Mr. Levy, told the judge: “A concerted attempt is being made, apparently by a well-known national newspaper, to bring pressure to bear upon a witness not to give evidence.” The prosecution claimed to be appalled, with Mr. Christmas Humphrey’s stating in response:

“I offer my friend protection to that witness day and night until that person has given evidence.”

By the 17 November 1949, Brian D. Hume was clearly paying close attention to every detail of his trial. He had already begun writing while he was being held in jail, but he was soon making detailed notes during the trial which he used to instruct his counsel. He carried an inch thick shorthand notebook and two freshly sharpened pencils and, with his one foot lodged between the iron railings of the dock, it was reported that he was taking notes in longhand.

The case had become the talk of Britain and the family of Stanley Setty were soon in the public eye again when they were accused of having still not paid Mr. Sydney Tiffin the £1,000 reward money which was originally offered for any information leading to the discovery of Stanley Setty, dead or alive. They eventually paid Tiffin by 23 December just under a month later, although the payout came with a stipulation that if any other parts of Stanley Setty were found, no more reward was to be made available. With Hume still pleading not guilty, the trial was heading to the infamous Old Bailey after the magistrates hearing at Bow Street decided the case should be committed for trial. The trial of Brian Donald Hume for the murder of Stanley Setty was expected to be long.

Before 4 October, Hume had apparently been hard up for cash, but in his opening statement at the murder trial, the prosecutor, Mr Christmas Humphrey’s would state:

“Thereafter Hume was found to be in possession of a quantity of £5 notes which on his own confession, corresponded in numbers with the numbers of notes that had been published in the press.”

After the murder of Stanley Setty, once Hume had cleaned up the blood and better wrapped parts of Setty’s corpse, he tied a rope around the bundle to make it easier to carry. Hume gave evidence that while he was moving one of the packages down the stairs of his flat, it began to make “a gurgling noise,” stating:

“I thought it was a human body, that of a small man or a young person, and it crossed my mind that the package might have contained Setty’s body as I had read in the papers that he was missing.”

When Hume’s landlord, Martin Collins, who was a greengrocer and fruitier located in Golders Green, came to collect the rent owed sometime between the 5-7 October, he noticed that Hume had quite a lot of £5 notes. In court Collins told the jury: “I said to him ‘Blimey, Bill, you’re doing alright. Share them out.’” Hume also found himself in need of a much sharper carving knife, going to a local ‘garage hand’ and panel-beater employed at Saunders Ltd., Maurice David Edwards of West Hendon, who would ‘rough-grind’ the knife for Hume, stating in court that Hume was in a hurry and “would not wait for a better job to be made of it ‘because he wanted to get back to carve a joint.’”

Mrs Ethel Stride also appeared in court. She was described as Hume’s ‘charwoman’ – a woman hired to clean and do odd jobs as and when required – and explained that Hume had requested she buy another floor cloth, claiming that he had used hers to wash his carpet. When asked by Mr Humphrey’s: “Did Hume go into the kitchen?”, Mrs. Stride told the court that:

“He said he was tidying up a cupboard in the kitchen to make room for coal to be stored for the winter, and he said he did not want to be disturbed. ‘On no account and in any circumstances?’ – These were his words as near as I can remember.”

However, Mrs. Stride later made Hume a tea in the scullery and she entered the kitchen, where she said that she had seen no signs of a man’s torso, no signs of blood, and where she heard no noise like the sawing up of bones.

The package still remained too heavy for Hume to tackle alone, and so he would hire Joseph Thomas Staddon, a painter, on 6 October to apply wood stain to some of his sitting-room floor. When Staddon arrived, Hume also asked him if he’d help him take the package downstairs. Staddon told the court that: “It was about 2ft. 6in. long, roughly 18in. wide and 1ft. high.” The painter went on to tell the jury: “It was very heavy. I could not lift it myself. I was going to put my hands underneath it and lift it down, but Hume stopped me and told me to carry it by the rope.” Hume told Staddon that the package contained ‘valuable property’. On 18 January 1950, with a lots of evidence in court centering around Hume’s home, the jury of ten men and two women visited Hume’s flat in Golders Green.

During the trial at the Old Bailey, Hume remained under close observation in a hospital cell in Wormwood Scrubs. As the trial reached it’s climax, the accused man was reported as acting strangely by the prison guards who had been tasked in keeping him under constant watch.

One of the most interesting and important witnesses to be called was Dr. Robert Donald Teare, who had been the pathologist to examine the torso of Stanley Setty. He suggested that the wounds on Stanley Setty’s body were unlikely to have been caused by an attack from just one assailant. He went on to tell the court at the Old Bailey that the absence of bruising and marks on the body of Stanley Setty suggested that he was killed by more than one person. Dr. Teare was supposed to be the final witness at the enthralling trial of Brian Donald Hume and he stated that if Setty had been attacked by a single man, he’d expect the event to involve a struggle resulting in a lot of noise, stating:

“I would expect either considerable resistance on the part of the attacked man, resulting, in all probability, in injuries to his body in the way of defence, or protective injuries to hand or arm, or I should expect a volume of blood to be distributed over the assailant and walls, furniture and floor.”

Instead, Dr. Teare posited that Setty was most likely restrained from behind whilst he was stabbed, leaving no bruising or defensive injuries. Responding to the defence counsels questioning, led by Mr. R. F. Levy. K.C., Teare said:

“I think the absence of marks of defence upon the body renders it more likely he was killed by more than one person.”

Mrs. Cynthia Hume, wife of the accused, had previously stated that it would have been “quite impossible” for her husband to have murdered Setty in their flat on that fateful evening and for her not to have heard a commotion, although she did also admit that she didn’t know how her husband made a living.

Regardless of Teare’s strong belief that the evidence pointed at multiple assailants, the Police Inspector who examined Hume’s flat said in court that the bloodstains were “entirely consistent with a man having been killed there”. But, regardless of how much evidence was piling up against Hume, Teare’s expert testimony had a massive effect on the trial. The explanation given by Teare had given credence to Hume’s tale of Max, the Boy and Greenie. There was suddenly a narrative which, with the help of one of the most experienced and esteemed pathologist’s in London, cast serious doubt on the prosecutions case against Brian Donald Hume.

Towards the end of the trial, Mr R. F. Levy announced that the case he was making was closed except for his final statement but, in fact, Levy had one last surprise witness. On 25 January 1950, Mr. Levy called Douglas Clay, of Gloucester Avenue, St. Pancras, who said he was employed as a writer. Clay told the court that the previous February he had been in Paris, where he had met a gang who smuggling arms to Palestine and cars to Britain. The testimony of Clay was recorded in the Evening Standard:

“Two of the men he particularly remembered. They were on “general duties,” but generally were strong-arm men. One was known as the Boy and the other as Maxie.”

Clay testified that he had never seen Hume in his life and Mr R. F. Levy, KC, in his closing speech for the defence in the murder trial of Stanley Setty, told the jury:

“I submit to you with every confidence that that man was murdered not by one man, but by several, And there you have ‘Mac,’ ‘The Boy’ and ‘Green’ – not a question of finding one alternative to Hume, but of finding a number of men.”

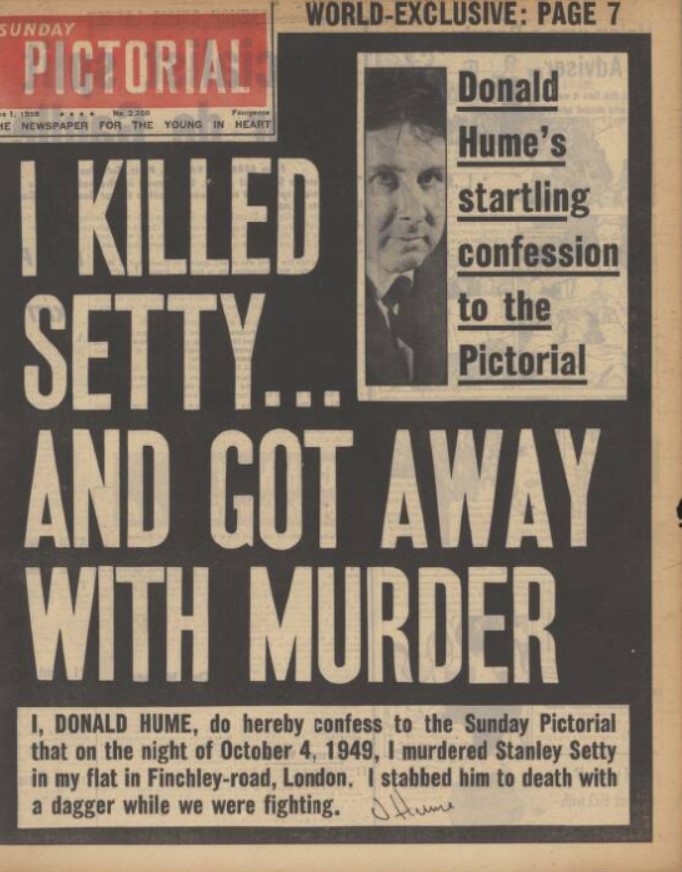

The trial of Brian D. Hume had come to an end with another massive plot twist. The final closing speeches in the case were made on 26 January 1950 and the jury were sent away to deliberate over a verdict. The defence tactics had been extraordinarily successful. Until the testimony of Dr. Teare and Mr. Clay, Hume’s fate was almost completely sealed, but the jury had been filled with doubt. Later on 26 January, the jury returned with a verdict. Brian Donald Hume was found guilty of being an accessory to murder after the fact and sentenced to twelve years in prison. When the jury returned at 3:03pm to deliver their verdict in the charge of murder, the judge asked them: “Have you any communication to make?” to which the foreman replied: “We are not agreed.” The jury could not reach a unanimous decision concerning the murder charge. Mr. Christmas Humphrey’s had consulted with the Director of Public Prosecutions before making a final decision, but the decision had already been made, with Humprey’s stating:

“After full consideration my view is that it is not necessary in the interests of justice that there should be a retrial of this indictment, Therefore, I respectfully ask a jury should be sworn and then no evidence will be offered on this indictment.”

The trial was over, and although he was heading to prison for 12 years, Brian Hume had got away with the actual murder of Stanley Setty. The trial itself had been remarkable for several reasons. Hume had faced three juries in total; the first were discharged when Justice Lewis fell ill; the second was re-sworn but failed to agree, and; the third was sworn in and offered no evidence on the charge of murder.

Even though Hume was just starting a hefty prison sentence, he seemed desperate to remain the centre of attention. By 5 February, the Sunday Pictorial, which became Hume’s publication of choice for releasing stories, released an admission by Hume of illegal arms smuggling to Israel. In the article entitled ‘I Was an Arms Smuggler,’ Hume claims that he had helped smuggle various equipment to the newly found state of Israel. He even published a hand written list of the various arms he claimed to have trafficked with the list including; a Spitfire plane; a converted Halifax Bomber; walkie-talkies; anti-tank guns; cases for mustard gas bombs; and lorry loads of boots. On 12 February 1950, it was printed in the Sunday Mirror that the recently imprisoned Hume “weeps and storms” like a caged animal, with Fred Redman reporting:

“If he has more to tell – if the story he has told so far is anything less than the whole truth – then he is ripe to tell it now.”

Redman was right, Hume was clearly ready to spill every mysterious bean he had ever stored up inside himself.

In the second installment of this two-part series, we’ll investigate Hume’s claim of atomic espionage, knowledge in the Rillington Place murders, and, once he is released from prison, his full and astonishing public confession to the murder of Stanley Setty. The British legal system had failed the Setty family, and there were more victims to come, as Hume’s murderous antics had not yet come to their conclusion.

<READ PART 2 HERE: Black Hand #7 – The Murder of Stanley Setty Part 2: Confessions of a Dangerous Man>